Bevan and the NHS, 1945-1948

| Matters found unsatisfactory |

|

| Boundaries in the south east | |

| The effect of the election | |

| The definition of regional boundaries | |

| References |

Until 1945 the safest assumption in London was that the hospital services would be based upon the local authority, with a regional advisory council to coordinate planning with the counties surrounding the capital. The Conservatives had produced a White Paper along these lines in 1944. Labour’s election victory in July 1945 led to a dramatic change. Aneurin Bevan, the new Minister of Health, had wide responsibilities including the problems of post-war housing. Nevertheless he moved rapidly and within days was submitting lists of questions for his civil servants to answer. He took quiet soundings from professional bodies and associations, and senior civil servants soon came to understand the new Minister’s thinking.1 Bevan believed that the state should guarantee a free health service for all2, which automatically deprived the voluntary hospitals of their traditional sources of money. Public funding implied public control. Bevan had at his disposal a wide range of expert reports; service considerations were covered by the hospital surveys, which confirmed the haphazard growth, the unevenness and the deficiencies of the existing arrangements; there was a report on medical education from Goodenough, and reports on London from the county council and the joint coordinating committee.

Bevan's proposals

Bevan took radical new proposals to Cabinet in October 1945. His chief opponent was Herbert Morrison, a defender of local government in general and the London County Council in particular. Bevan’s scheme excluded local authorities from a role in hospital management, for he had come to believe that as 80% or more of the cost would fall upon central funds, full central control was needed. Local government already had enough to do. National ownership would be combined with regional planning and local administration. With the exception of the teaching hospitals, which would have boards of governors directly accountable to the Minister, hospital services would be managed by regional boards on his behalf. The regions would be based upon university medical centres, ‘the natural focal points of specialist medicine and therefore of the hospital services’.

In January 1946 the proposals were circulated on a confidential basis to key associations and interests. Bevan did not intend to reopen the long drawn out discussions of the previous four years, and the confidential meetings he held with the local authority associations, the British Medical Association, the King’s Fund and the British Hospitals Association were not so much for the purpose of consultation, but to prepare people for what was to come.1 The British Hospitals Association, once it was aware of what was in the wind, chaffed at the temporary ban on wider discussion. The details were made public on 19 March 1946 when a summary of the National Health Service Bill was presented to Parliament. Sir Bernard Docker, the chairman of the Westminster Hospital and of the British Hospitals Association, opposed the plan at once, saying that it was not in the interests of the patient to eliminate all sense of local pride, interest and responsibility in local hospitals, as must be the case if local management committees were autocratically appointed and made responsible only for minor day-today affairs. Lord Latham, the Leader of the London County Council, said that his council had devoted much thought and effort to the task of making its hospitals the finest in the world, and it was therefore with great reluctance that the council would see them pass into the ownership of the state. However the council would insist that the interests of the people of London were fully safeguarded by adequate council representation on the proposed regional hospital boards.

As far as the hospital service was concerned, the new proposals went a long way to meet the desires of the medical profession and the voluntary hospital movement. The doctors had feared a salaried service, with loss of clinical freedom. This risk had been averted, and to the avid socialist Bevan’s scheme appeared almost reactionary. The voluntary hospitals had looked for a way to preserve their independence, though dependent on public funds. They had therefore opposed local authority control, seeking instead partnership on a management body alongside the representatives of local government. This had been achieved. A regional solution was in sight, within which university hospitals would have a special place. Indeed the British Hospitals Association wrote to Bevan that ‘so far as concerns the arrangements for the general administration and financing of the service we are satisfied that a substantial measure of common ground is already in sight’.4

The issues likely to prove sticking points for the London voluntary hospitals were the ‘seizure’ of the hospitals by the state, endowments and trust funds, and regional boundaries. Sir Bernard Docker and the British Hospitals Association remained violently hostile on these matters throughout the negotiations. The Association raised with Bevan ‘the crucial question of ownership ... by involving the extinction of entity, confiscation, elimination of personal interest, and a most autocratic method of appointing persons at all levels for the provision and management of hospital services, the present proposals bear no relation to our accumulated experience or to the historical evidence of achievement of voluntary as compared to other hospitals.’ The King’s Fund presented its case more sensitively when its representatives met Bevan on 5 February 1946. Bevan agreed to examine the question of the retention of the endowments of the teaching hospitals.1 The Fund subsequently wrote to the Minister pointing out the importance of independence of management of the individual hospitals, and the need to find some acceptable arrangement whereby the funds of the hospitals might be respected. The Fund said that only in a few cases, such as St Bartholomew’s, Guy’s and St Thomas’s would the income be substantial, and these institutions were of such importance to the future that they could certainly be trusted to spend the money wisely. Much in Bevan’s scheme had proved to be entirely in line with the views of the King’s Fund.4, 5

Sir George Aylwen (London Voluntary Hospitals Committee and St Bartholomew’s) was present at one of the early confidential discussions and wrote to Bevan asking whether existing boards and board members could be retained, and for clarification of Bevan’s intentions for the endowment funds of the teaching hospitals. Bevan replied that the new boards would be designed to include the more valuable members of the old ones and that he intended ‘the reconstructed teaching hospitals to enjoy the various endowments vested in them’.

And what about historical treasures? Guy’s was worried about the fate of an almost unique set of Hepplewhite chairs - would they be snatched away to the Victoria and Albert for the benefit of the nation as a whole? An assurance was given that the value of historical tradition was appreciated, and no such action would be taken. The summary of the Bill confirmed that the endowments of the voluntary teaching hospitals would pass directly to the new boards of governors.6

Before he took the chair at a meeting of representatives of the London voluntary hospitals, Sir George Aylwen wrote again to Bevan to ask for ‘a local solution’ for the trust funds of the smaller voluntary hospitals. He hoped that the Minister would reconsider the question, to enable him to ‘influence at least the London hospitals to give you that measure of support which will so definitely be needed in the early stages’. Bevan replied that it was part of his deliberate purpose to redistribute income to regional boards to reflect ‘the actual needs of each rather than the largely accidental effect of past benefactions’. However he agreed that further moneys collected up to the start of the National Health Service could be held on a local basis.1,4

The senior members of the London County Council had used their influence to pacify their colleagues. In the course of a debate in April 1946 Lord Latham said that he and his party deplored the taking away of the LCC hospitals and the encroachment upon local government. But one quarter of the hospitals in the country were voluntary and the remainder were municipal, and the government had decided to take over the voluntary ones. There could not be two systems, and the only way was to combine both into one unified and comprehensive organisation. He did not believe that the people of London would wish the council, either directly or indirectly, to sabotage the National Health Service for narrow, selfish interests.

Bevan was faced with the need to balance the claims of many opposing interests. During the committee stage of the Bill, he told Parliament that he had been careful to devise a scheme which gave teaching hospitals the utmost autonomy. Most were delighted because their financial situation would be infinitely better. Traditions would be preserved. Bart’s would still be Bart’s and Guy’s would still be Guy’s. But if every teaching hospital in London went on record against the scheme it would still go through. Though it was not a threat, he would like some teaching hospitals to bear in mind that if they insisted on some modifications, other modifications might also have to be made, less to their liking, to increase the enthusiasm for the scheme in other quarters.7

Most teaching hospitals appreciated that they had much to gain. The financial state of many had indeed been parlous until their survival had been assured by wartime subventions. Under peacetime conditions difficulties would recur. Two-thirds of the income of St Thomas’s Hospital in 1947 came from state or local authority sources, and the situation was much the same at Guy’s and the other teaching hospitals. While they feared the loss of autonomy associated with ‘nationalisation’, ‘municipalisation’ would have been worse. One of the St Thomas’s staff wrote that had the hospital had the power to decide its own fate in a national health service, it could hardly have chosen better than to follow the course laid down for it by Parliament.8 Boards of governors were comparable in size to the previous management committees, and not dissimilar in membership—although doctors were now members of all boards as of right. The sometimes substantial endowment moneys had been preserved, and the boards were corporate bodies with the power to hold land and property and act as principals carrying out functions on behalf of the Minister. The burden of debt had been lifted and the extent of local autonomy was considerable. In a memorandum sent to all chairmen the Minister said that they were to enjoy the largest possible measure of discretion. He wanted them to feel ‘a lively sense of independent responsibility’. Planning would be a process of continuing informal consultation between the board, the university, the teaching hospital and the Minister. Many of Bevan’s appointments preserved continuity with the past, although in a few cases like the Westminster Hospital it was clear that the previous chairman would be totally out of sympathy with the new order, and a new man was essential.

The smaller voluntary hospitals were in a less happy position. They were to lose a larger measure of their independence and would in future be managed by regional hospital boards alongside the municipal hospitals upon which they had looked down. They were asked to make no plans for their future, pending the establishment of the regional boards which would determine the future pattern of services in each locality. Their financial position was also precarious. Sir Austin Hudson, writing on behalf of the Metropolitan Hospital, said: ‘Like all hospitals, we have always run on an overdraft from the bank, taking care that it did not get too large, and by means of special appeals at not too frequent intervals.’ Bevan’s announcement had dried up all the large subscriptions and made an appeal impossible; yet the cost of running the hospital had increased as a result of the introduction of national salary scales. The bank was now pressing the Metropolitan to repay its overdraft. The Ministry’s reply confirmed that overdrafts as well as assets would be taken over on the appointed day. If hospitals were in immediate financial difficulties they could utilise remaining assets, or the Ministry would examine their situation. The King’s Fund raised the same problem with the Minister, and Bevan replied that some hospitals might have to incur overdrafts or eat into their capital, but that financial assistance could be offered to those in difficulties.9 His reassurance was circulated to the hospitals by the British Hospitals Association.

Regional boundaries in the south east of England

The question of trust funds had been settled rapidly. Another problem, unique to the south east, remained. The nature of regional boundaries in London and the home counties became the subject of a bitter fight between the voluntary movement and the London County Council. The emotion and energy expended on this question is at first sight surprising, since patients are able to cross boundaries for treatment at will. Deep feelings were clearly involved.

Since 1900 legislation had increasingly placed vast responsibilities on local government. In 1940 the London County Council provided about 40,000 general hospital beds and another 35,000 in mental illness hospitals, making it the largest hospital authority in the world. The quality of the council’s hospitals, the size and excellence of the voluntary hospitals, and the council’s attitude to regionalisation created problems in London which did not exist elsewhere. It was one thing to consider regional councils and cooperation by committee in rural counties where the services were in any case often deficient; in London traditions and attitudes were different.

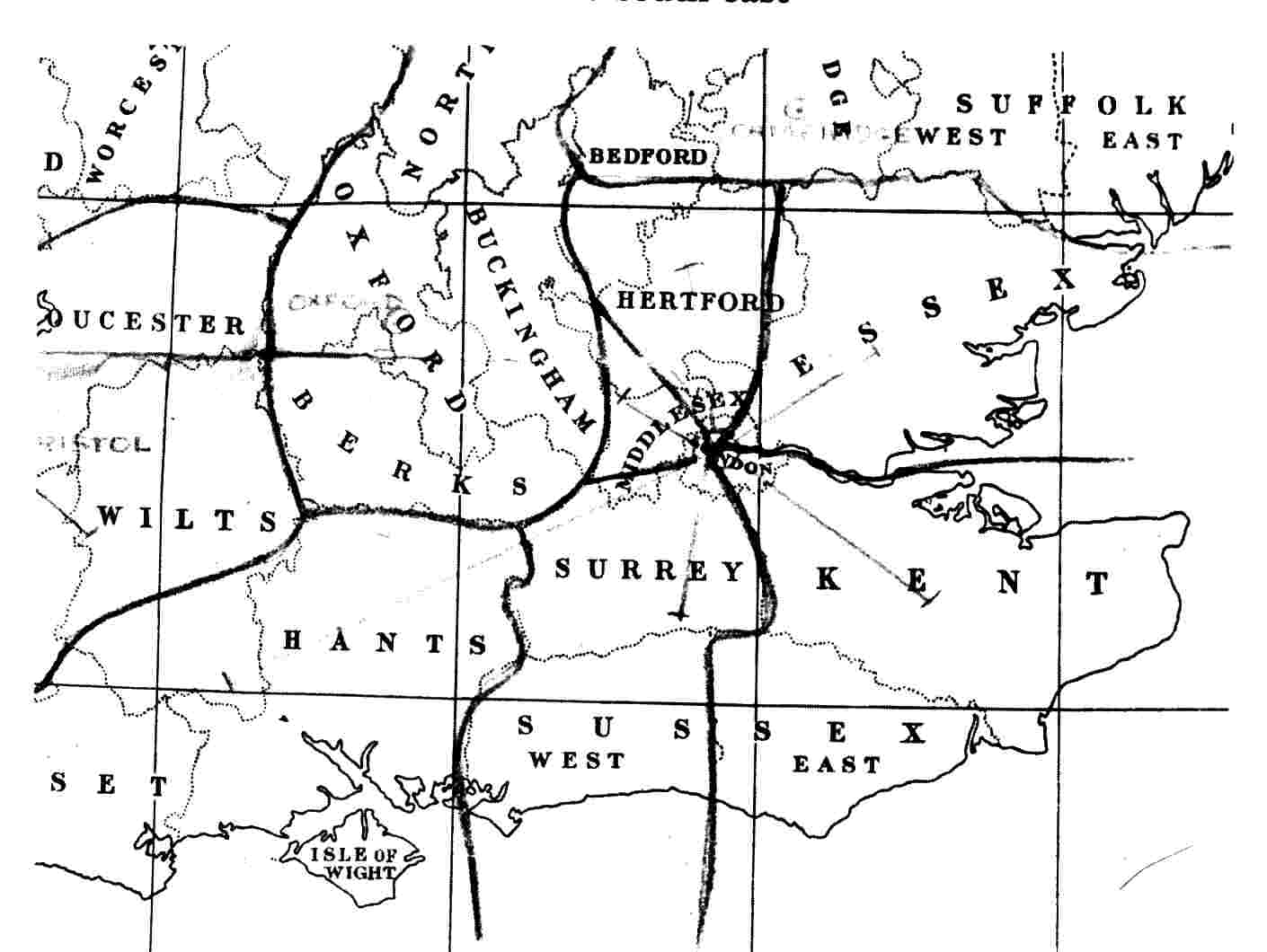

Sir Frederick Menzies had drawn attention to a further complication. London had the advantage of the King’s Fund, but the Fund’s area was not a local government one. It was the Metropolitan Police District, which covered the administrative county of London but which penetrated deeply in ‘starfish’ pattern into each of the home counties. The area of the Metropolitan Police District was several times that of the administrative county, and it was in Menzies’ view an impossible area for any form of voluntary hospital and local authority cooperation.10 Yet Menzies’ successor, Sir Allen Daley, had once said that on a purely medical basis a sector system was probably best. It was the relationship of medical services with other council services which led him to prefer a central London region. Lord Latham, as Leader of the London County Council, make his position clear to ministers in March 1943. He hoped that the administrative county of London would be regarded as a sufficiently large unit of administration for the new hospital service.

By early 1941 the London Voluntary Hospitals Committee recognised that whilst regional councils were being established in many parts of the country, London was playing no part in the movement. A subgroup of the committee considering the possible repercussions on the voluntary hospitals of regionalisation accepted that London was a particularly difficult problem. The LCC was unique as a hospital authority, a large number of voluntary hospitals could justifiably claim to be regarded as key hospitals, and local authority areas did not match the spheres of influence of the large hospitals. Nevertheless, the subgroup considered that regionalisation was as necessary in London as elsewhere, although it could not be achieved without LCC cooperation. The most suitable area was, in its opinion, the administrative county of London plus the adjoining home counties of Essex, Hertfordshire, Middlesex, Surrey and, possibly, Sussex. Whether or not the LCC was willing to cooperate, the group suggested that the voluntary hospitals should get a regional scheme into operation for themselves.11

Menzies, now retired, agreed. However he thought the King’s Fund area should be extended to cover all the home counties. The Nuffield Trust, believing that the local authorities in the home counties would not be prepared to work with the LCC, proposed a London region consisting merely of the administrative county and Middlesex.12, 13

The policy of the King’s Fund was first clearly defined on the publication of the White Paper on a National Health Service in 1944.14 The Fund said that the London region must cover part or all of the home counties.15

‘The White Paper contains a hint that it will be necessary to have regard to administrative convenience, and implies that the area of the London County Council will constitute a single authority. The experience of the King’s Fund in the Metropolitan Police District proves unmistakably that such an arrangement would only perpetuate one of the primary sources of maldistribution of hospital facilities in the metropolitan area. Insofar as there is a lack of adequate hospital services in the London area, it is to be found on the periphery of London where populations have sprung up in recent decades, where it has proved difficult for voluntary provision to keep pace with the growth in population, and where the local authority has equally failed to meet the situation. If ever there was a case for coordinated planning, it is over this wide area which transcends the County boundaries.’

When the White Paper was debated in the House of Lords, the Earl of Donoughmore repeated the King’s Fund’s argument. If the area of the London County Council was to become the basis of London’s health service, he said, it would be flying in the face of experience. The Emergency Medical Service had not confined itself to London, and treated other things outside as separate.

‘If the London County Council area is to be the hospital area by itself, what is to happen to the hospitals in the City? What is to happen to those in the County of Middlesex, and those parts of Surrey, Kent, Essex and Hertfordshire which are worked in with the London hospitals? ... What is serious is this, that the hospitals of London want great extension, but the places where the extensions are wanted are not in the centre and I doubt whether they are in the London County Council area - they are in the periphery where there has been an increase in population. Whatever is done in London, reorganisation has to be based on hospital needs, not based on geographical accidents which arose in days gone by through totally different causes.” 16

The importance attached by the Fund to university influence was explained by Lord Donoughmore at a meeting with the Minister, Mr Henry Willink, in March 1945. The Fund wondered whether it would not be possible to devise planning areas radiating outwards from central London? The Minister agreed that there must be a regional council to coordinate the plans of a wide area, including central London, but thought that proposals to split the metropolitan area on a sector basis would result in considerable difficulties ‘which could hardly be faced in connection with the forthcoming health legislation’.’ Nevertheless, on 25 July 1945 Sir Bernard Docker wrote to Lord Donoughmore at the Fund to say that the British Hospitals Association had met representatives of the British Medical Association and found that they were in agreement that domination by the London County Council must be avoided, that there were dangers in a single planning area coterminous with the county council boundary, and that a ‘cuffing the cake’ method of dividing the south east would be best, associating ‘a definite and natural part of the periphery with the centre.'15

The effect of the general election on boundaries

For a few weeks after the 1945 election, policy remained the unification of Middlesex and the administrative county of London, discarding sectorisation because it would be as necessary to plan for patient-flow across sector boundaries as across county boundaries. It was argued that the close link between London and the adjoining areas was due to their inadequate services which had enforced dependency on London. Planning on a sector basis might stereotype a defective system, and the aim should be to provide specialist services in the outer areas.

But as Bevan’s ideas about the future health service developed, and the proposal to take all hospitals into public ownership emerged, the significance of local authority boundaries waned. The ‘bondage of boundaries’ was broken, and regionalisation became the keynote. Everybody got it firmly into their heads that the essence of a region was that it focused on a university teaching hospital and its medical school; one could hardly have a region which did not have a medical school. It was well recognised that the natural region for hospital and health service purposes extended over practically the whole of the south east of England, with a population of fourteen million compared with populations of three or four million for the regions envisaged for the rest of the country. The surrounding areas of cities like Liverpool and Manchester were dependent on their university hospital just as the south east was dependent on London; but in London the difference in size was so great as to present a different problem.

Towards the end of 1945, Ministry officials were drawing rough maps of regional boundaries, in the south east arranged on a radial basis. The early maps showed five regions, three north of the Thames and two south.

But in January 1946 when Bevan circulated his provisional proposals for the health service on a confidential basis he referred to ‘about twenty natural areas of regions for hospital organisation’ without any precise indication where their boundaries might lie. On 20 January 1946 he met the negotiating committee of the medical profession. Amongst the many questions, he was asked for an assurance that the area of the regional board or boards for London would not be the administrative area of the London County Council. Bevan immediately answered ‘yes’.17 He repeated this statement to the King’s Fund on 5 February 1946.’

Source: PRO/MH/80/29 Crown copyright reserved

On 16 April Reginald Stamp, chairman of the Hospital and Medical Services Committee of the LCC, wrote to Bevan with two requests. Pointing out that he and Lord Latham had done much to secure support for the Bill from the LCC and the Associations of County Councils and Municipal Corporations, Stamp asked that personal and domiciliary services should remain with the Council rather than with the boroughs. Bevan replied that he wanted to be as helpful as possible on that point.18 Stamp’s second request was more significant. ‘You have been considering breaking London up into 5 Regions’, he wrote.

‘I beg of you not to reach a final decision on these lines now and to study closely the alternative. I have considered it very carefully and am convinced that unless you make the County of London one Region you will not get a good scheme and may even find the five regions attached to the provinces won’t work smoothly. Further, you will play right into the hands of the Voluntary Hospital and Medical Profession people, who wanted to do this under the old scheme to break the power of the LCC. I know the personnel available in London and Home Counties areas and I would say that if you have 5 regions with London in each, you will simply not have the effective personnel to work the Regional Boards. My friends and I can’t physically serve 5 of them and the medical profession and the voluntary hospital people will hold full sway.’

Bevan signed his reply the day his officers were due to confer with local authority representatives. Sir Arthur Rucker’s advice was that much as one would like to meet the LCC who had done so much to meet the Ministry, the assurance sought by Stamp was impossible to give. Bevan’s reply said that to make the London County Council area a hospital region in itself would be utterly inconsistent with the whole conception of the Bill as far as hospital services were concerned. One of the main objects of the proposed new regional administration, and the taking over of hospitals everywhere, was to enable organisation to follow natural functional boundaries. It would defeat that object completely to adopt the county boundary of London as demarking a separate region. He was not making up his mind yet what the actual regions affecting London might be, and he would want Reginald Stamp’s help and that of many others when the time came; but he could not possibly accept the suggestion made.

The LCC, controlled by Labour for many years, had not expected such treatment from a Labour administration. There was a feeling of hurt that not only were its hospitals to be taken away but the boundary of the region would not be its own. In April 1946 the Hospitals and Medical Services Committee of the LCC considered a carefully argued paper and recommended to the council that it should:

i Aim for a London or central London region including all LCC hospitals and any others outside which London needed.

ii Try to get 50 per cent of the regional hospital board members appointed in consultation with the LCC.

iii Aim to get 50 per cent of the hospital management committee members representative of the LCC.

On 26 April 1946, Sir Arthur Rucker met local authority representatives, including seven from the London County Council. The LCC pointed out the difficulties of a smooth change-over if existing services were not allowed to carry on substantially as working organisations. Sir Arthur made it clear that the council’s proposals ran counter to ministry policy. It was contemplated that there should be nothing in the nature of a central London region and that, indeed, substantial reorganisation in central London would be carried out. The question was one of major policy and if the council disagreed with this line it should make its representations to Parliament.

During the second reading, Bevan said that the local authority area in London was an example of being too small and too large at the same time. He regarded administrative boundaries as a matter he should determine, and not an issue for the consideration of Parliament. This was challenged at the committee stage of the Bill, and whilst Bevan won by 20 votes to 17 he subsequently agreed to define regional boundaries in regulations to be submitted to Parliament, once the Bill had passed through all stages and become law.

The definition of regional boundaries

Under Bevan’s scheme local authorities and their boundaries had become less significant. The Ministry now argued that the regional system was designed purposely to avoid adherence to local authority boundaries in hospital planning, and that ‘London was the case par excellence for ignoring the county boundary, which was without meaning as demarking any special group of persons or type of district, which cut across normal flows of population by rail and road, and included a far larger proportion of hospital provision than was proper to the population of the county. The perpetuation of the London County Council area as a unit could scarcely fail to arouse the suspicion that the existing system was being continued, and that the voluntary hospitals were to be “sold” to the London County Council or its successor. The way would, in fact, be paved for a reversion to county council management were there to be a change in political policy.’

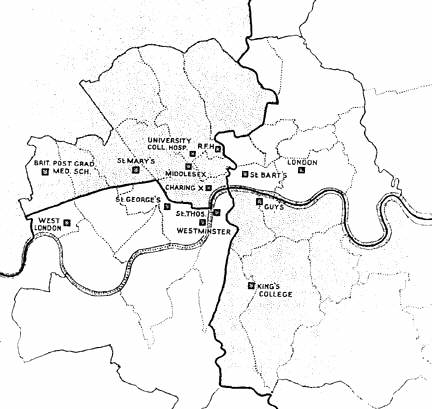

Once the National Health Service Bill had been published, discussions on regional boundaries began to take place more openly. There was little difficulty in defining regions outside London. With only one teaching hospital per region, boundaries were not too difficult to draw. But in London twelve teaching hospitals had to be catered for somehow or other. Applying the principle of a university focus, the only solutions were a massive region or a sector system based upon groups of teaching hospitals. For advice the Ministry turned to the only group which had experience of managing all the hospitals in the south east - the group which had managed the Emergency Medical Service and its London sectors. The first meeting of the ‘London syndicate’, as it became known, was held on 4 December 1945.19 The Ministry was represented by Dr John Charles, a deputy chief medical officer, and the members were Sir Claude Frankau, Sir Francis Fraser, Sir Ernest Rock-Carling and Sir Archibald Gray. The constitution of the group enabled it to take account of both educational needs and the problems of running a hospital service.

In April 1946 the London County Council submitted its proposal for a central London region. The arguments adduced were continuity of service, the easier job of a county council which could relate to one region rather than five or six, and the fact that a radial division of the south east of England would make a coordinating body necessary to consider the problems of London as a whole. Opponents of the council’s plan argued that a central London region would undermine trust and goodwill of the voluntaries, risk the perpetuation of ‘the existing unwieldy machine’, and establish a precedent for other parts of the country. By May the syndicate had concluded that the difficulties of radial sectors had been exaggerated and further discussions in June and July centred on two alternative schemes. In Scheme A, four regions for London and the south east each included a number of metropolitan boroughs. In Scheme B, only two of the four regions contained parts of the London County Council area, the north east (19 boroughs) and the south east (10 boroughs). Scheme A was chosen and, with minor revisions, was adopted by the syndicate on 7 November 1946. The National Health Service Act had now passed all its stages and time was pressing if the order was to be laid before Parliament before the Christmas recess. On 9 November the submission went to the Deputy Secretary, Sir Arthur Rucker, and on 15 November Bevan discussed it with senior officials including the chief medical officer, Sir Wilson Jameson.20

Source The Lancet 1946, ii., pp 842—4, 879—80.

Bevan agreed the proposals on 15 November and they were issued for consultation that day, with a month allowed for comment. It was thought unlikely that changes would have to be made as a result of consultation, and in London but not elsewhere this proved the case. Simultaneously the regional hospital boards were christened, and in London they were named metropolitan hospital boards. In most parts of the country county boundaries had remained intact, but not in London. Sir Allen Daley wrote a letter of protest to Sir Wilson Jameson and Sir Arthur Rucker. To his colleagues in the home counties he wrote: ‘our county is split into four in an extremely arbitrary fashion dictated solely by the need to apportion twelve teaching hospitals among the four regional areas. The Ministry’s officers have no idea of the complexities of hospital administration ... if they go about it like iconoclasts destroying what is good instead of building up from it they are heading for disaster.’ Sir Allen was not being entirely fair, for some care had been taken to adjust the four regions so that the populations were approximately equal and no region was overloaded.

Sir Allen Daley reported the position fully to the General Purposes Committee of the London County Council on 27 November 1946, and made an attempt to rally his medical officer of health colleagues to fight the proposals. With Dr Macaulay of Middlesex County Council, and Dr Patterson from Surrey, he attended a syndicate meeting on 7 December but nothing was gained. Surrey County Council decided to make no observations on Bevan’s proposals. Daley hoped that Kent and Middlesex would support the London County Council and, after a careful briefing session, members and officers of the county councils met Bevan on 13 December.21 The LCC representatives said the proposals would subdivide the local health authorities and metropolitan boroughs. The geographical areas of the regions were too large, united services which had taken many years to build up would be disintegrated, and there would be grave transitional problems. The council suggested an entirely different arrangement, a central London region surrounded by four home counties regions. Bevan said that he found the discussion depressing, for local authority boundaries had nothing to do with the hospital services. Regional boards were confined to hospital purposes, and local authorities had no right to have wounded feelings because county boundaries were to be ignored. Bevan agreed that there would be a need for a coordinating committee between the four regions because of London and Greater London problems, and officials were left to pursue this. But on the key issue Bevan gave no ground. The LCC representatives subsequently reported to the Council that the interview had been ‘unsatisfactory’.

The University of London had no comment to make upon the proposed division of London, save to note that the teaching hospitals were unevenly divided between the regions, with six in the north west. Several of the medical schools submitted their views; St Bartholomew’s wanted the regional boundary moved west, even though this would bring the Royal Free and UCH into the same region. St Mary’s and Charing Cross also thought that this would be a good idea. The London Hospital Medical College wanted to be in a region by itself. King’s College Hospital wanted Croydon included in the south east region. The Lancet had doubts as to the wisdom of splitting London arbitrarily into four zones and feared that the London end of the regions would be the tail which wagged the dog. Perhaps London should have a region of its own.23

The King’s Fund said that the proposals were fully in accord with the views it had expressed from time to time. However it drew attention to the suggestions of the Voluntary Hospitals Committee for London, which included the transfer of the Royal Free Hospital and University College Hospital to the north east region. Bevan acknowledged the letter which he said would receive very careful consideration. At the end of the consultation period he wasted no time. Five days later, on 20 December 1946, a statutory order was laid before Parliament.24 A final meeting between Bevan and the London County Council took place on 25 February 1947, after which Lord Latham reported to the council that the Minister had not been willing to modify his proposals. However, Bevan had agreed to set up machinery, with which the council would be associated, for the coordination of the work of the four proposed regional hospital boards and the local authorities in other areas. On this understanding the Council had decided not to take action in Parliament over the order, and had agreed to assist the Minister in dealing with problems of supplies.25

There the matter rested, but the local authorities did not forget that their boundaries had been ignored. Sir Allen Daley’s annual report said little about the transfer of the council’s hospitals to the regional boards, although two of the council’s officers were congratulated on their appointment as senior administrative medical officers. Of the other two metropolitan posts, one went to the Medical Officer of Health of Middlesex, Dr Macaulay, and only one - the south east metropolitan job - to an ‘outsider’. The establishment of the National Health Service had an immediate effect on many organisations whose objectives would now be a matter for the state. Most voluntary hospitals had associated Samaritan funds, organisations of ‘friends’ and other bodies engaged in charitable, fund-raising and social activities. The wives of members of the staff were often involved, and not only did they raise sizeable sums, they provided corporate spirit.

The British Hospitals Association, which had represented the interests of the voluntary hospitals at national level for the previous thirty years, could not continue its traditional function. Although it was consulted about the membership of the regional hospital boards it had no further role to play and was wound up in March 1949.26 It had never been a rich organisation and it only had assets of a few thousand pounds. Partly in its place, representatives of Guy’s and St Bartholomew’s founded the Teaching Hospitals Association in 1949.

The Charity Organisation Society’s functions spread far beyond the hospitals; it was renamed the Family Welfare Association. It continued to help families in difficulty, aiming to remove the cause of distress and not to merely deal with immediate need. Hospital Saturday continued to provide health insurance and financial benefits for subscribers. The revenues of the Metropolitan Hospital Sunday Fund had been diminishing and it decided to make grants available not as in the past for maintenance but to provide additional amenities.

The King’s Fund had far greater resources. The four metropolitan boards asked it to continue to run the Emergency Bed Service and to plan its extension with them. With reserves of between five and six million pounds the Fund could use its moneys in new ways to promote progress in directions outside the immediate purview of the state hospital service. One initiative was to establish a bursary scheme to recruit and train young administrators, posting them to teaching hospitals for practical experience. In addition the Fund now had a wider constituency which included the old municipal hospitals. It was free to foster those things which make a hospital a human and sympathetic place, rather than merely an efficient machine.5

1 PRO/MH/80/29 and 34; PRO/CAB/129 no 5 page 159 onwards.

2 Bevan A. In place of fear. London, MacGibbon and Kee, 1952.

3 Daily Telegraph, 22 March 1946. British Medical Journal, 1946, i, p 582.

4 PRO/MH/77/78.

5 Today and tomorrow. London, King Edward’s Hospital Fund, 1947.

6 Great Britain, Parliament. The National Health Service Bill. London, HMSO, 1946. Cmd 6761.

7 Parliamentary Debates (Hansard), House of Commons, Standing Committee C, National Health Service, 22 May 1946, columns 217—220.

8 Sharpington R. No substitute for governors. London, St Thomas’s Hospital, 1980.

9 PRO/MH/77/79.

10 Menzies F. Memorandum to the Ministry, August 1941.

11 Voluntary Hospital Committee paper VHC 585, October 1941.

12 King’s Fund A/KE/100.

13 King’s Fund A/KE/224.

14 Great Britain, Ministry of Health and Department of Health for Scotland. A National Health Service. London, HMSO, 1944. Cmnd 6502.

15 Statement of principles and memorandum on the White Paper, London, King Edward’s Hospital Fund for London, 1944. A/KE/355.

16 Parliamentary Debates (Hansard), House of Lords, 21 March 1944, columns 147—53.

17 PRO/MI-I/80/32 (NHS(46)7).

18 PRO/MH/77/82; British Medical Journal, 1946, i, p 582.

19 PRO/MH/99/40.

20 PRO/MH/90/1.

21 London County Council Papers, PH/GEN/l/26.

22 PRO/MH/90/4.

23 Lancet, 1946, ii, pp 842—4, 879—80.

24 Statutory regulations and orders 1946, no 2158; King’s Fund A/KE/410..

25 Minutes of the London County Council, March 1947.

26 Papers of the British Hospitals Association, 1948—9, held by the library of the London School of Economics.