| The Royal Commission | The Second Green Paper (1970) |

| The Todd Working Party | |

| Coordinating the coordinators | |

| Approaching the (1974) NHS reorganisation | |

| The first Green Paper (1968) | References |

By the mid-sixties, London’s hospitals had got over the initial upheaval of the introduction of the National Health Service. Financial allocations were increasing year by year, relations with the Ministry were reasonable, and new services could be offered to patients. Planning to rebuild three teaching hospitals further from the centre of London was at an advanced stage. Most of the undergraduate teaching hospitals had accepted a district hospital responsibility and a joint consultative committee had been established in each quadrant of London. However not all was sweetness and light; some tensions persisted between boards of governors and regional boards. The planning of regional specialties, if not non-existent, was certainly ineffective. Finally, while earlier reports like Guillebaud1 and the Acton Society Trust papers2 had concluded that the basic organisation of the service was sound, there was increasing criticism of its tripartite structure. In 1967 the Minister, Mr Kenneth Robinson, announced that he planned to issue a consultative paper on the administrative arrangements in the National Health Service, and in London hospital staff knew that they would also be affected by a forthcoming report on medical education. Change was in the air.

The Royal Commission on Medical Education3

The proposal to establish a royal commission was made by the University Grants Committee in the early sixties. A memorandum written to its medical sub-committee argued that there was a need to tackle three problems which could not be solved by the sub-committee alone. They were the organisation of postgraduate education, which required not only efficient training but its association with the university education recommended by Goodenough; the problem of London where half the country’s medical students were educated; and the further expansion of medical education. In London it had proved difficult to increase the contribution of university medicine within the teaching hospitals, where there was resistance to making room for clinical academic units. Money from the University Grants Committee therefore tended to go into the provincial schools. The many semiautonomous bodies, both service and academic, made it difficult to obtain the agreement necessary for any major change. Dr John Ellis, physician to The London, a member of the medical sub-committee of the University Grants Committee, and a part-time principal medical officer at the Ministry, was the author of the original memorandum. In his Schorstein lecture4 he listed the recommendations ultimately made by the commission which were specific to London:

The number of pre-clinical places in London should be increased from around 800 to 1,200 in the first instance, to allow maximal use to be made of the country’s greatest concentration of medical resources.

The number of medical schools should be reduced from twelve to six by pairing them, so as to allow pre-clinical departments of a viable size and each school to have access to a full range of clinical departments, adequately staffed.

Each paired medical school should come into association with a multi-faculty college so as to enable the teachers in the medical schools to have close contact with teachers in other university disciplines, and vice versa.

Money should be provided to start filling the gaps in academic staffing.

Postgraduate institutes should come into association with the paired medical schools so as to end the isolation of the former and provide the latter with academic staff in the specialties.

General responsibility for the implementation of the plan for London should be placed in the hands of a committee with representation from the university, the UGC, and the health authorities, with an independent chairman, and the committee ‘should remain in being long enough to ensure that, in future developments, short term convenience is not allowed to nullify long term planning’.

The commission reaffirmed many of the principles laid down by Goodenough, and it did so at a time when people were more inclined to pay attention than they had been in the midst of war in 1944. It accepted Goodenough’s assessment of the clinical facilities required by students and thought it would be desirable for the medical schools to have access to patients in the new hospitals which were being built away from the centre of London. Paired schools would have an annual clinical intake of around 200 students and would need access to about 2,000 beds. The commission calculated that by 1976 the areas for which the teaching hospitals accepted ultimate responsibility, and in which the students would be taught, would have a population of 2.8 million so that virtually all hospitals in central London would be needed for teaching. It was accepted that all hospitals should be managed within the framework of regional authorities, discontinuing the system of boards of governors.

St Bartholomew’s Medical College and The London Hospital Medical College;

University College Hospital Medical School with the Royal Free Hospital School of Medicine;

St Mary’s Hospital Medical School with the Middlesex Hospital Medical School;

Guy’s Hospital Medical School with King’s College Hospital Medical School;

Westminster Medical School with Charing Cross Hospital Medical School;

St Thomas’s Hospital Medical School with St George’s Hospital Medical School.

Many of the medical schools objected to the pairings. Guy’s and King’s held discussions without commitment on either side. Over the following months the University Grants Committee, London University and the Department of Health and Social Security considered the report, and in August 1969 simultaneous statements were issued by the Department and the academic authorities. The academic bodies accepted the first four pairs but proposed to associate St Thomas’s with the Westminster. Charing Cross and St George’s were left unpaired because the university and the Department agreed to ignore the recommendations and stick to the plans to rebuild them at twice their previous size.

The Department considered that there was scope for reorganising the clinical services between pairs of teaching hospitals, and that as far as possible the service links should follow those of the medical schools. However it did not see that St Thomas’s and the Westminster could be paired sensibly for health purposes, as one served areas to the south of the Thames and the other to the north. Instead the Department proposed that each should coordinate its services with other hospitals on the same side of the river.5

Implementation of the recommendations

While many of the medical schools would have liked to secure the future by expanding their intake, the University Grants Committee and London University were alert to the danger, for much of the increase in students recommended by the commission would be absorbed by St George’s and Charing Cross. Expansion came mainly in the early seventies, when the deteriorating financial situation made it plain that the development of new or greatly expanded provincial schools was out of the question. The target of 1,200 was reached without the completion of the building work which had been thought necessary. The university and the University Grants Committee required each of the medical schools it was proposed to pair to form joint policy committees, and a university steering committee was formed to foster developments. The essence of pairing was the formation of joint academic units, often in emerging subjects, rather than rebuilding. Considerable progress was made at The London and St Bartholomew’s, but many schools resisted closer association. The postgraduate institutes, in particular, were united and effective in their resolve to resist association with a general medical school. Neither were the undergraduate hospitals always enthusiastic. University College Hospital and the Middlesex, under the influence of Sir Max Rosenheim, had been discussing closer cooperation. The proposal that University College Hospital Medical School should associate with the Royal Free instead received little support in any quarter. Money to permit the recruitment of academic staff which the royal commission had considered necessary was initially lacking. However the University of London received a significant addition to its revenue in the early seventies, allowing a considerable number of new chairs to be established in the schools. Virtually no attempt was made to ‘pair’ these posts.

The Todd working party for London

The royal commission had recommended the formation of a committee for medical education in London, with an independent chairman and members, and representation from the University Grants Committee, the University of London and the Department of Health and Social Security. This was rejected by the university, and not until 1971 was the Todd working party for London assembled. It was chaired by the Permanent Secretary of the Department and consisted of a very few representatives from senior levels of the three bodies. The delay in forming the working party, which was meant to ensure that short-term convenience did not nullify long-term planning, resulted in a situation in which the possibility of a long-term plan insured that short-term progress was difficult.

The plans for rebuilding Charing Cross, and later St George’s, were given the go-ahead, undermining further the royal commission’s scheme. It was agreed to begin work on sketch plans for ‘UCRF’ (the medical schools of University College Hospital and the Royal Free), and ‘BLQ’ (the medical colleges of The London Hospital, St Bartholomew’s, and Queen Mary College). However, ‘KTW’ (King’s College, St Thomas’s Hospital Medical School and the Westminster Medical School) was a more doubtful starter as the site costs were high &id the development would take some time to bring to fruition. The relocation of the Westminster Hospital and its school at Roehampton, Guildford, Croydon or Brighton was considered, and postgraduate associations were examined at considerable length, for there were many practical problems in moving and rebuilding them to bring them into closer association with the commission’s pairs. Most of the schemes were costly, involved building on over-crowded sites, or led to an inappropriate pattern of service (see below). Once the effects of the impending economic crisis came to be appreciated the commission’s proposals began to appear increasingly unrealistic. A century had passed since The Lancet suggested, in 1870, that medical schools should amalgamate, with little progress having been made.

Construction of the three teaching hospitals, which were relocated

|

|

Contracts let |

Work on site |

First admissions |

|

Charing Cross Hospital |

1967 |

1967 |

11 January 1972 |

|

Royal Free Hospital |

1 January 1968 |

June 1968 |

1 October 1974 |

|

St George’s Hospital |

19 January 1973 |

1 March 1973 |

January 1980 |

Implementation of the Royal commission recommendations as reported to the Todd Working Party in 1973 |

|||

| Hospital and institute | Associated hospital | Proposals | Ultimate outcome |

| Hammersmith and Royal Postgraduate Medical School | King Edward's Ealing | Development in Ducane Road suggested | |

| Hospital for Sick Children and Institute of Child Health | Bart's and The London | Redevelopment on site announced in 1973 | |

| National Hospital for Nervous Disease and Institute of Neurology | Probably UCH and the Royal Free | Redevelopment on site announced 1973 | |

| Royal National Throat, Nose and Ear Hospital, and Institute of Laryngology and Otology | Middlesex/St Mary's or Royal Free | Redevelopment on Middlesex site at a later date | Later joined UCH |

| Moorfields and Institute of Ophthalmology | Bart's and The London | Redevelopment on Bart's site | Remained independent |

| St John's and Institute of Dermatology | Middlesex/St Mary's | Redevelopment on Middlesex site | Later joined St Thomas' |

| Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital and Institute of Orthopaedics | Middlesex/St Mary's | Redevelopment on Middlesex site | Remained independent |

| St Peter's and Institute of Urology | Bart's and the London | Redevelopment on The London site | |

| Queen Charlotte's and Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology | King Edward's Ealing | Rebuilding at Ealing | Associated with Hammersmith |

| Royal Marsden and Institute of Cancer Research | Concentration at Sutton | Remained independent | |

| Eastman Dental Hospital and Institute of Dental Surgery | Middlesex/St Mary's | Rebuilding at St Mary's | Associated with UCH |

| St Mark's | Bart's/The London | Rebuilding on Bart's site | Moved to Northwick Park |

| Did not happen as proposed |

At his conference in 1965, Mr Kenneth Robinson had raised the possibility of far reaching changes in the administrative structure and had asked the four joint consultative committees to consider the establishment of a forum to consider health and welfare problems of London as an entity. One committee, that of the south east, replied a few months later that such a step would be premature, for on present experience the ordinary methods of consultation were adequate. However, in June 1965, the Permanent Secretary, Sir Arnold France, wrote to say that the government might take powers to place certain teaching hospitals under a specially constituted hospital management committee, itself responsible to a region. This seemed likely in the case of Nottingham where a new medical school was under development.6

The Teaching Hospitals Association was almost unanimous in its opposition to this idea. Sir Desmond Bonham-Carter drafted a memorandum to inform the Ministry of Health of the strongly held view that the direct access to the Ministry enjoyed by boards of governors was so valuable that it had to be preserved at all cost. Goodenough, Guillebaud and Porritt had all concluded that teaching hospitals should be administered separately, and that a high standard of medical education could best be maintained by very close links with academic medicine. This depended upon the constant and intimate links of hospitals with medical schools. Regional boards were preoccupied with a wide variety of problems and could not be expected to give a proper measure of support to teaching hospitals, or encourage an adequate concentration of skills. Sir Desmond hoped that an alternative solution might be found to the problems peculiar to London.

In November 1965, Sir Arnold France proposed a conference of teaching hospitals and regional boards. The chairmen of the South East Metropolitan Regional Hospital Board, of Guy’s, King’s and the Maudsley, wrote jointly to say that it was unnecessary and undesirable to make statutory change in the relationships between their authorities. Their committee had been successful in solving problems and had shown unanimity of purpose; the machinery already in existence was best geared to producing the results desired. Nevertheless the chairmen recognised that some problems faced each quadrant of London which could not ‘be wholly and unwastefully resolved individually’, and they welcomed the possibility of an advisory body to which the four joint consultative committees could refer problems when wider consultation was necessary. The Minister replied that he had an open mind on hospital administration in central London and decisions could not be made until the Royal Commission on Medical Education had reported. Just before the conference on 30 January 1967, Dr James Fairley, the senior administrative medical officer of the South East Metropolitan Board, drafted a proposal suggesting that the existing machinery should be strengthened by the addition of a standing joint advisory committee to coordinate the four regional joint consultative committees.

He submitted the proposal to the Ministry just before the hospitals and boards met to discuss the experience of the four regional committees. The chairman of the north east committee was afraid that the functions of the regional boards might be usurped, but there was wide agreement that coordinating machinery was necessary. Fearful that control of the new body which was being proposed might fall into the hands of the Ministry, James Fairley circulated his suggestions widely and submitted them to The Lancet, which rapidly published them.7 They received considerable support, and when the Ministry produced its own document in May 1967, a coordinating body similar in nature was suggested. This was later to become the Joint Working Group of the Thames Joint Consultative Committees. Fairley became the secretary and driving force of the new group, which was chaired by Dame Albertine Winner, a recently retired deputy chief medical officer of the Ministry. The key issue was whether the group should be given the teeth to influence planning through control of financial allocations. There was resistance to this, as a result of which the group was less effective than it might have been.

The new group took over responsibility for a study of radiotherapy which was already in progress. It also produced a series of reports on the main specialties, including accident and emergency services, ophthalmology, neurosurgery, cardiac surgery, audiology and ear, nose and throat disease, psychiatry and mental handicap.8 The reports broke new ground by examining requirements on a London-wide basis, taking into account bed numbers, length of stay, occupancy and turnover interval. Some reports made firm recommendations for the closure of units, or cast doubt upon the need for redevelopment. The neurosurgery report made it clear that facilities in London were adequate, and a new joint unit which three teaching hospitals were planning was unnecessary. Other reports provided population projections, or promulgated principles which the four regional joint consultative committees could apply within their own quadrants. The implementation of the recommendations was the weak point, for neither the regional boards nor the boards of the teaching hospitals were bound by them. As a result, the Ministry came to question the desirability of a free-standing body independent of the hospital authorities.

Reorganisation of the hospital service was in the air. In November 1967, Mr Kenneth Robinson announced that he intended to review the administrative machinery of the NHS, looking particularly at its tripartite structure of hospital services, family practitioner services and local authority health services. He pointed to the existence of the Royal Commission on Local Government9, and to the Seebohm Committee on Local Authority Social Services.10 A number of parallel activities was in progress; the Royal Commission on Medical Education was nearing the end of its work as was the Salmon Committee on Senior Nursing Staff Structure.11 At the time of his announcement staff within the Ministry of Health were already considering the details of a proposal to abolish regions and replace them with 40 to 50 area boards - and the way in which this concept could be applied to London. The next five years saw a succession of attempts to define a better pattern of organisational structure, and the resistance of groups who feared that they would be placed at a disadvantage.

The appearance of so many reports was in itself the cause of problems. For example the Royal Commission on Medical Education reported before the Ministry’s proposal for area boards was known. If the University of London moved fast and amalgamated medical schools, should the pairs be placed under the existing regional hospital boards, or if area boards were just over the horizon would it be better to avoid two upheavals by delaying until the area boards were in place? The possibility that teaching hospitals might benefit from a change in governance found little acceptance amongst the chairmen and officers of the boards of governors, or in the forum of the Teaching Hospitals Association. The direct link with the Ministry was highly valued. While some hospitals like University College Hospital, under Sir Desmond Bonham-Carter who was also the chairman of a regional hospital board, and Charing Cross which was secure in its new development, viewed assimilation into a region in a relaxed way, others like Guy’s took a harder line. They felt that regions would swallow them with the result that services of high quality would be levelled down. Nevertheless a common front was displayed in public. The possibility of uniting hospital and community health services under the same authority increased the significance of boundaries, which had been less important when only hospital-based services were involved. Local authorities, and the Inner London Education Authority regarded boundaries as of crucial importance; those concerned with hospital administration believed that hospital ‘districts’ depended primarily on transport patterns.

Following the publication of the reports of the Seebohm committee or local authority social services and the Royal Commission on Medical Education, Kenneth Robinson published his Green Paper on the administrative structure of the NHS in July 1968. The Paper proposed that regions should be abolished, to be replaced by a single tier structure with forty to fifty area boards. The teaching hospitals would lose their independent management bodies, the membership of their area board being specially adapted to the teaching responsibilities. Not surprisingly there was opposition. The regions felt that the Ministry was ill-equipped to deal with as many as fifty areas, and that the areas would be too remote to manage the hospitals effectively. Dr James Fairley thought that amendment of the existing structure would be preferable13, the new proposals being particularly difficult to apply in London, where a coordinating body directly accountable to the Minister would inevitably be required. He thought that the possible submergence of university hospitals was to be avoided if the cuffing edge of British medicine was not to be blunted.

Determines financial

allocations and general policies;

plans specialised services;

secures coordination of areas; provides guidance on standards

A single authority in each area to replace executive councils, regional hospital boards, boards of governors and hospital management committees Serve from ¾-2 million; plan and operate services; provide financial, staffing, support functions and management services

Meeting to consider the double impact of the Royal Commission on Medical Education and the Green Paper, the Teaching Hospitals Association agreed on five principles: the need for a direct relationship both with the Ministry and with their associated medical school; the right to appoint their own staff; adequate financial allocations; and continuing responsibility for their endowment funds. The association’s chairman, Sir Desmond Bonham-Carter, was also chairman of University College Hospital and the South West Metropolitan Regional Hospital Board and his colleagues were well aware that he believed that teaching hospitals should be brought under the regions. He resigned.

To study the pattern of area boards that would be desirable in London a working party was established by the Ministry, chaired first by Lady Serota and later by Lord Aberdare. London boroughs had changed their boundaries in 1965, reassuming responsibility for community health services from the London County Council. Two alternative patterns of area boards were suggested in the Green Paper. One was a ‘starfish’ with five area boards each serving two or more inner boroughs and several outer London boroughs. Populations would be about 1.5 to 1.75 million and the arrangement would accord generally with the Todd pairs. The alternative was a ‘doughnut’, with the cream in the middle. There would be two teaching area boards, one north and one south of the river, surrounded by four areas for outer London. The five or six area boards would cover between them the whole of the Greater London Council area, and the need for a mechanism to provide for collaboration was recognised.

The teaching hospitals had little enthusiasm for either proposal, based as they were on a desire to follow local authority boundaries, and the loss of boards of governors. A memorandum prepared in September 1968 by the Teaching Hospitals Association questioned the advantages which might come from a new and untried structure. However, if reorganisation was to come, the association would prefer the doughnut arrangement, or a single board for all of inner London with continuation of the existing system of joint consultative committees. The Ministry, for its part, tended to favour a ‘starfish’ organisation; the Royal Commission on Medical Education had also settled for a radial solution. The commission had suggested a fifth north central region to reduce the complexity of the management of a large number of teaching hospitals by any one region.

When the Royal Commission on Local Government in England reported, it suggested that the possibility of unifying responsibility for the NHS within the new system of local government should be considered; failing that the commission wished to see coterminosity of health and local authority areas, but did not support either the ‘starfish’ or the ‘doughnut’ conclusively.

Richard Crossman, as Secretary of State, had to conduct negotiations on his predecessor’s Green Paper. There were three strong criticisms: the risk that the areas would be remote from day to day activity, the possibility that boards would be dominated by the hospital service, and the absence of provision for regional planning. Mr Crossman met regional chairmen and the Teaching Hospitals Association in November 1969 to discuss the form a second Green Paper might take. The government subsequently announced its decisions on the Report of the Royal Commission on Local Government, rejected the management of the health service by local authorities, but decided that in general the number and areas of the new health authorities must match those of the new local authorities. that area authorities should remain directly accountable to the Department of Health and Social Security, but added regional health councils to undertake those activities for which the areas were too small. In the south east there would be four regional councils, covering much the same areas as the metropolitan boards. A coordinating body would be created as a successor to the joint working group. It was suggested that there might be five inner London areas and 10-12 covering the rest of the capital. The London working party was asked to consider the new proposals, but by this time the teaching hospitals were becoming rather cynical about the whole procedure, and its emphasis on borough boundaries.

The proposals of the second Green Paper, 197014

|

Department of Health and Social Security

Strengthened

regional liaison function which allocates funds directly to and

deals directly with area health authorities; plans

and executes major building schemes |

|

|

Area health authorities________________________________ Population 200,000- 1.3 million; neither supervised nor controlled by regional councils; free to establish area consortia at will |

Regional councils Members appointed by areas, professions and university; undertake planning and determine the priority of competing developments; plan regional specialties and postgraduate education; in London the metropolitan councils might be coordinated by a group like the joint working party; medical staffing |

|

District committees (if the area is large)

Perhaps 200

natural districts in all; membership half area members, half

local; no separate budget or statutory delegated powers;

supervise the running of the service |

|

|

The five London areas suggested were: Tower Hamlets, Hackney and the City of London; Camden and Islington; Westminster, Kensington and Chelsea, and Hammersmith; Wandsworth and Lambeth; Southwark and Lewisham |

|

Consultation on the second Green Paper was affected by a change in administration. The new Conservative government came to the conclusion that some of the proposals were sound but others were not. Sir Keith Joseph, the new Secretary of State, announced that the government was not satisfied that the 1970 proposals would create an efficient structure for a unified service. A new consultative document was issued in May 197115, which proposed that instead of regional councils there should be regional health authorities responsible for general planning, allocation of resources to area health authorities, and the coordination and general oversight of the latter’s activities. Study groups were rapidly established to consider management arrangements and the way in which the health service and local authorities might cooperate.

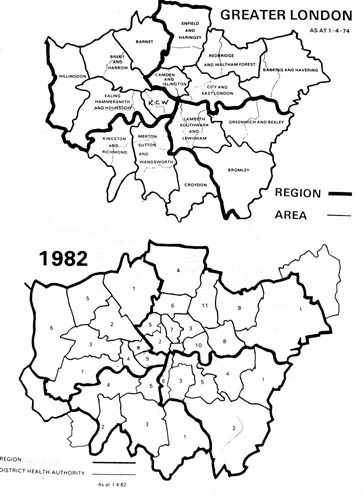

Regional boundaries were reviewed. The cost and complexity of the recommendation of the Royal Commission on Medical Education for the establishment of a new north central region became apparent. Five regions were also considered undesirable because of the sacrifice of continuity. One region for the whole south of England would be too large. Two regions, north and south of the river, or two north plus one south, were also discussed. A two region arrangement would make it unnecessary to set up coordinating machinery for the London area. Keeping the number of inter-regional boundaries to the minimum would help strategic planning, and simplify the problem of the postgraduate hospitals, most of them being north of the river. However the size of the regions, if there were only two or three, would increase the complexity of management at a tune when regional responsibilities were being widened. The view which prevailed was that a single authority for Greater London would produce an undesirable concentration of specialised health services and deprive the surrounding regions of essential facilities. The creation of viable regions around London would be difficult without running contrary to the natural lines of communication. It became accepted that a four-region structure would persist, but the application of the principle of coterminosity - that health and local authority boundaries should match - meant that adjustments had to be made to the regions. The Department proposed that the north west/south west boundary should be moved south to the river, that Camden and Islington should move into the north east region, and the whole of the borough of Lambeth should be included in the south east region.

|

The Starfish and the Doughnut Two alternative patterns of regional boundary are a ‘doughnut’which is concentric, and a ‘starfish’ with a radial arrangement of boundaries and communications. The arguments in favour of the doughnut concept were:

The arguments against the doughnut were:

|

The London working party continued to spend much time exploring the points of view of the bodies it represented. The London boroughs showed great reluctance to part with their share of the NHS. In any event they wished the new health authorities to match boroughs on a one-to-one basis. The executive councils wished to preserve their large areas of administration on the ground of efficiency. The Greater London Council argued the case for a regional planning unit corresponding to its own area. The regional boards wanted to perpetuate the metropolitan regions stretching out from London into the home counties. The teaching hospitals were unable to find common ground with the other parties, rejecting coterminosity and disliking the thought of officer-management at hospital or district level. They favoured a sector scheme with larger areas, so that they were not ‘shut up in London’;16 each sought a population of around 300,000 to meet its educational requirements. The Teaching Hospitals Association thought more time should be allowed to study the problem in London, and commissioned SCICON to undertake a study of the appropriate ‘boundaries for health care’.17

The likelihood of agreement being reached by the working party was slight. However the Department felt a sensible compromise was beginning to emerge. Time was pressing and quick decisions were needed if health service reorganisation was to take effect on the same day as local government reorganisation, 1 April 1974. It was felt that reasonably sized, self-contained teaching areas could be formed from grouped London boroughs. Each would have two or more districts, not necessarily coterminous with the boroughs, the management within the districts resembling the pattern elsewhere in the country.

Consequently on 29 March 1972 the Department issued new proposals for the creation of regional and area authorities in London18, allowing six weeks for consultation. The Department accepted that the problem was difficult, and not capable of an easy solution satisfactory to all parties. Sixteen areas were suggested for Greater London, with a London Coordinating Committee to assist the planning of facilities for teaching and research, and the regional and sub-regional specialties. SCICON suggested an alternative pattern with comparatively few areas of substantial size, an approach which reduced the need of patients to cross into another area to obtain a full range of services, and related teaching hospitals more closely to the districts from which they drew their patients.17

The White Paper on reorganisation appeared in August 1972.19 The Lancet said that it was ‘welcome and wise, and that the future looked bright.’20 The White Paper set out the government’s decisions on the changes necessary to establish an integrated service. In general they were similar to those proposed in the consultative document, but instead of area health authorities being required to set up a teaching district committee for districts containing substantial teaching facilities, there were to be area health authorities (teaching) with specially constituted membership.

The postgraduate hospitals managed to avoid radical constitutional change. In June 1971, Sir Keith Joseph wrote to Lord Cottesloe to say that Lord Aberdare’s working party was coming to the view that it would not be possible for the postgraduate hospitals to be managed by area health authorities (T) from April 1974 and that their boards should continue for a period of five years. This would allow time for the development of convenient associations between the postgraduates and other hospitals. Subsequently the Teaching Hospitals Association commissioned SCICON to undertake a further study on the functioning of postgraduate hospitals and their relationship to other parts of the health service.21

The four joint consultative committees were clearly going to be unnecessary once the regions took over responsibility for the teaching hospitals. Some of them ceased to meet. However the Department had recognised the need for a coordinating group which was advisory in nature; it could not be an executive body or there would be conflict of authority with the regional health authorities. The Teaching Hospitals Association told the Secretary of State that it regarded such a group as important, and there were debates about the role and composition of the new body. The joint working party had shown something of a tendency to determine matters of health service policy for itself, rather than rely on expert advice. There had also been a lack of commitment to its recommendations. The main role for a new London coordinating committee would seem to be rationalisation of the work of hospitals in central London, including the postgraduate ones; coordination of regional specialties; coordination of work in central London where patients frequently crossed regional boundaries; and the inter-relationship of service and teaching needs. In the meanwhile a group of Departmental officers were at work and after two years produced a plan for inner London hospitals which set out a pattern of district general hospitals thought appropriate for the new health authorities. This was sent to hospital authorities and other interested parties in October 1973.

Reorganisation was to create a radically different situation, much of which not to the liking of the teaching hospitals. The Teaching Hospitals Association had fought to retain their autonomy and their direct link with the Department and had lost. Teaching hospitals no longer had their own management bodies and authority membership was removed from the point of local activity. Hospital administration was undertaken by officers responsible to a more distant area. Larger groups of hospitals were created, with all the consequent problems of management and maintenance of esprit de corps.22

When the area boundaries were announced the application of the coterminosity principle meant not only that two or three boroughs matched each inner London area authority, but two or three teaching hospitals might be placed under a single management body. Guy’s, St Thomas’s and King’s College Hospital fell within Lambeth, Southwark and Lewisham AHA(T), and the Westminster, the Middlesex and St Mary’s were managed by Kensington, Chelsea and Westminster AHA(T). The London and St Bartholomew’s were managed by the City and East London AHA(T), and Charing Cross and the Hammersmith by Ealing, Hammersmith and Hounslow AHA(T). Each of the four Todd pairs accepted by the Department lay within a single area, but other hospitals which were not part of that pair might be included. Teaching hospitals faced the future with apprehension, fearing that they might be swallowed up in a larger and more impersonal organisation.

The new management bodies were not like the old ones. Some of the members had experience of the old regime, but a significant group owed their place to membership of local authorities. Before extinction the boards of governors, appreciating that in future no authority would have the same close association with individual hospitals, recognised the need for an alternative body to hold and administer the endowment moneys. Guy’s took the lead in negotiations with the Department of Health, and as a result the Act contained a provision for the establishment of special trustees in respect of hospital endowments.

The era of ‘lively independence’ for the teaching hospitals had been brought to an end by the integration of the three branches of the National Health Service: the hospitals, general medical services and local authority health services. A period of tranquillity was now needed to allow the health service to become used to the new arrangements. This was not to be. In the last three months of 1973 the Oil Producing and Exporting Countries (OPEC) imposed a substantial rise in the price of oil. A period of industrial unrest was followed by a general election, and by a new administration in March 1974. The new Labour government was out of sympathy with some features of the reorganisation about to take place, but felt that it could not be postponed. In any case there was a desire to try to make the new system work.23

1 Great Britain, Ministry of Health and Scottish Home and Health Department. Report the committee of enquiry into the cost of the National Health Service. (Chairman: C W Guilebaud). London, HMSO, 1956. Cmd 9663.

2 Hospitals and the state, numbers 1-6. London, Acton Society Trust, 1955-7.

3 Royal Commission on Medical Education 1965-8. Report. (Chairman: Lord Todd). London, HMSO, 1968. Cmnd 3569.

4 Ellis J R. Medical education in London. Schorstein Memorial Lecture. London, London Hospital Medical College, 1979.

5 Great Britain, Department of Health and Social Security. Annual report, 1969. London, HMSO, 1969. Cmnd 4462.

6 The following account is based upon working papers belonging to the South East Thames RHA and the archives of Guy’s Hospital, the officers of which were prominent in the groups and committees which were established.

7 Fairley J. Administration of teaching hospitals. Lancet, 1967, i, p 328.

8 The annual and occasional reports of the joint working party of the four Metropolitan Joint Consultative Committees.

9 Royal Commission on Local Government in England. Report. London, HMSO, 1969. Cmnd 4040.

10 Royal Commission on Local Authority and Allied Personal Social Services. Report. (Chairman: F Seebohm). London, HMSO, 1968. Cmnd 3703.

11 Great Britain, Ministry of Health and Scottish Home and Health Department. Report of the committee on senior nursing staff structure. (Chairman: Brian Salmon). London, HMSO, 1966.

12 Great Britain, Ministry of Health. The administrative structure of the medical and related services in England and Wales. (The first Green Paper.) London, HMSO, 1968.

13 Fairley J. The Hospital, 1968, 64, p 398.

14 Great Britain, Ministry of Health and Social Security, National Health Service. The future structure of the National Health Service in England. (The second Green Paper.) London, HMSO, 1970.

15 Great Britain, Department of Health and Social Security. National Health Service reorganisation: consultative document. London, DHSS, 1971.

16 Holland W. Organisation of health services in London, Lancet, 1972, i, p 908.

17 Wellman F and others. Boundaries for health care in Greater London. London, Scicon, 1974.

18 DHSS letter to NHS authorities in London.

19 Great Britain, Parliament. National Health Service reorganisation: England. London, HMSO, 1972, Cmnd 5055.

20 Lancet, 1972, ii, pp 265-6.

21 Wellman F and others. The London specialist postgraduate hospitals. London, King Edward’s Hospital Fund for London, 1975.

22 Sharpington R. No substitute for governors. London, St Thomas’ Health District, 1980.

23 Great Britain, Department of Health and Social Security. On the state of the public health. Annual report of the Chief Medical Officer for 1974. London, HMSO, 1976.