|

‘A hospital is, of all social institutions, the one in which perhaps the greatest mixture of motives, the most incompatible ambitions and the most vexatious vested interests are thrown together' Langdon-Davies, 1952

The concept

of a hospital is a simple one to patients seeking care. To

those who work within them hospitals are worlds and empires

of their own. The groups working within hospitals have, on

the face of it, a common aim - but their interests are

divergent. As a result the reaction of a hospital to change

may baffle the outside observer, who knows little of the

pressure groups within its walls. This chapter considers

some of those groups, and issues of importance to them. The concept

of a hospital is a simple one to patients seeking care. To

those who work within them hospitals are worlds and empires

of their own. The groups working within hospitals have, on

the face of it, a common aim - but their interests are

divergent. As a result the reaction of a hospital to change

may baffle the outside observer, who knows little of the

pressure groups within its walls. This chapter considers

some of those groups, and issues of importance to them.Like other social services, London’s voluntary hospitals owed their foundation to charity. In the middle ages they were not solely devoted to the acutely ill; they also provided a haven for the lame, the blind, the chronic sick, the mad and the beggar. After the dissolution of the monasteries the citizens of London made a careful census of those for whom they wished to provide care. The royal hospitals included St Thomas’s, St Bartholomew’s, Bedlam, Christ’s Hospital and Bridewell. St Thomas’s and St Bartholomew’s took care of the ill, curable and incurable alike, Christ’s Hospital took foundling children, Bridewell the idle, and Bedlam the insane. Though both were closed at the time of the Reformation, St Bartholomew’s was re-endowed by Henry VIII as a result of a petition by the Lord Mayor of London, and St Thomas’s by Edward VI. A legacy of the Middle Ages, they were supported by estates confiscated from the Church but preserved for charity. Guy’s, founded in 1721, was maintained by the riches of that prudent speculator Thomas Guy and represented the philanthropy of modern commerce. All three could subsist on the income from their large investments without recourse to appeals to the public. They were therefore known as the ‘endowed’ hospitals. Otherwise there was little interest in the founding of hospitals until the early eighteenth century when it became increasingly common. A group of like-minded individuals might form a charitable association, with one or more medical men. The doctors might be professional leaders, like Cheselden who was on the staff of several hospitals. On the other hand they might merely be seeking a reputation. Simultaneously there were developments in medical knowledge and the role of the hospitals began to change. From being places of refuge they began to develop into institutions for curing, rather than care and comfort. Sometimes a single individual would follow Guy’s example and make a magnificent donation. In 1832 Captain John Lydekker left four of his ships to be sold for the benefit of the Seamen’s Hospital. But such men were uncommon, and the single pious benefactor gave way to groups of the wealthy and charitably inclined. The new hospitals were founded on a wave of philanthropy by those who wished not merely to alleviate distress but to restore the afflicted to respectable and independent citizenhood.

Like Guy's on the left, the great general hospitals came to

cluster, like the Pleiades, within the boundaries of

eighteenth century London. St Bartholomew’s and St Thomas’s,

north and south of London Bridge, were well sited for

Elizabethan London. Guy’s was built directly opposite St

Thomas’s by the wish of the founder. The Westminster, the

first of the new wave of voluntary hospitals, was founded in

1720 to meet the needs of the poor living nearby. With St

George’s, formed in 1733 by a group of doctors who seceded

from the Westminster and established themselves at

Lanesburgh House in the healthy air of Hyde Park, it

provided services to the West End for the first time. The

London Hospital (1740) was built in the east on the quiet

road leading from the City to the pleasant village of Mile

End for the poor of Aldgate and the adjoining riverside.

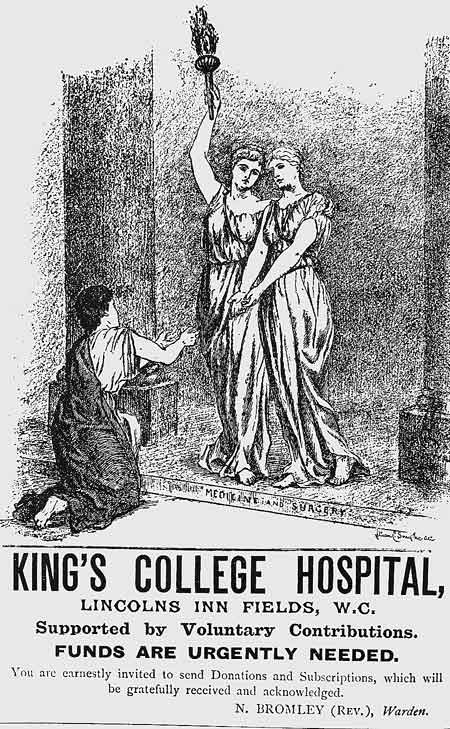

Shortly after, in 1745, the Middlesex was established to serve the sick and lame of Soho. By 1809 London could boast seven general hospitals, four lying-in hospitals, two for infectious diseases, the Lock Hospital for venereal disease and an eye hospital. By the early years of the nineteenth century the hospitals were developing yet another function. Not only were they treating patients but they were developing an educational and scientific role. A witness to the Select Committee on Medical Education (1834) said that the hospitals were amongst the chief sources of the advancement of medical science. They provided the best basis for the study of pathology and therapeutics, as long as the staff were up to standard. Three hospitals founded around this time reflected the new role. Charing Cross Hospital was developed in 1821 on the basis of a plan proposed by its founder, Benjamin Golding. From its outset Charing Cross was to combine a medical school and a charity for the welfare of the poor. University College Hospital and King’s College Hospital were also academic foundations, established close to the colleges it was their function to serve and to which they owed their creation. University College was founded in 1828 in the Benthamite and utilitarian tradition to provide a university education for the youth of the metropolis, without reference to religious creeds or distinctions. Wishing to establish a medical faculty, it presented land to a committee established to create a hospital by expanding an existing dispensary. The Lancet, which was critical of the standard of medical education in the existing hospitals, welcomed the establishment of the new North London Hospital which opened in 1834.2 It provided 130 beds to ‘improve the efficiency of the medical school, and serve the 250,000 residents around Islington and St Pancras.’ The Royal Free Hospital was founded in 1828 by Dr William Marsden on a principle then new for London’s hospitals. It provided treatment without asking prospective patients for a governor’s letter of recommendation, or expecting any form of payment from them. The need for treatment was the sole passport to admission. St Mary’s (1845) was a response to the needs of a local neighbourhood which ‘had grown immensely in population and wealth while remaining destitute of any adequate means of relief of the poorer inhabitants when suffering from accident or disease’. Its size was determined by examining the ratio of beds to population, members of the board studying the experience of the Assistance Publique on a visit to Paris. With a population of 150,000, it was calculated that Paddington stood in need of 376 beds. King’s College, an Anglican reaction against University College, had greater difficulty in finding a site for its students, and after seeking to utilise the clinical facilities of the new Charing Cross Hospital, it took over the old Strand Union workhouse. The medical press was less enthusiastic about this decision. ‘If a person well acquainted with London was desired to name its most unhealthy spot he would inevitably fix on that of Clare Market. Flanked by two grave yards, offal shops and human piggeries an old building has been selected by the wise and disinterested managers of King’s College for their hospital.’3 It was located ‘in an atmosphere impregnated with the effluvium of the dead, by shambles, brothels, disease and death’.4 King’s College bought a larger site nearby in 1846, but could not afford to rebuild until 1860. The great hospitals therefore had a variety of origins; some were ecclesiastical or charitable in origin, and a few were educational. Other smaller hospitals were also founded, often on the basis of an existing dispensary to which beds were added. The smaller hospitals might not be so wealthy, but they were proud of their reputation and often enjoyed Royal patronage; the Metropolitan Free Hospital, established in 1837, was supported by Prince Albert. Its object was ‘to grant immediate relief to the sick poor of every nation and class whatever may be their diseases, on presenting themselves to the charity without letter of recommendation; such letters being always procured with difficulty and often after dangerous delay’.5 A German doctor who visited London in 1840 remarked on the admirable cleanliness of the hospitals, the excellence of the provisions, the attention of the nurses, and last but not least the number and purity of the water closets. The criticisms he made were of the want of any central board of organisation, the difficulty patients had in obtaining admission if they did not have a governor’s recommendation, the restriction of admissions to one or two days a week, the insufficient frequency of the visits of the physicians and surgeons, and the small number of beds compared with the population in London when contrasted with the continental cities.6 The dispensaries Alongside the voluntary hospitals, which initially provided little in the way of outpatient care, lay dispensaries supported by charity to serve those of the sick poor whose condition did not require admission. Two were established around the beginning of the eighteenth century, but did not survive. The first to become firmly established was the Royal General Dispensary in Bartholomew Close, which was founded in 1770, amalgamated with St Bartholomew’s Hospital in 1932, and ultimately succumbed to bombing. In early days treatment was free, but the patient had to produce a letter of recommendation from a subscriber to the charity. At times a resident medical officer might attend patients on the district and the Eastern Dispensary recorded the district work in 1891 as including

Later dispensaries might ask patients for payment, perhaps for the medicine supplied, and others were established as part of a drive to form a chain of provident dispensaries to which potential patients subscribed on a weekly basis. Dispensaries, like hospital outpatient departments, might therefore compete with general practitioners and if they did not charge an economic rate they were looked on with disfavour. If they did levy a comparable charge, the dispensaries found it difficult to survive in the face of the competition of the free outpatient departments of the hospitals. Free, provident or private dispensaries sometimes came to specialise in particular conditions, and they might develop into a small hospital by the addition of beds. The teaching staff of the private medical schools often held an appointment at a dispensary, which was therefore used for teaching: and dispensaries might be stepping stones to a post at a major hospital.7 Dispensaries would issue certificates to students to say they had attended for the clinical experience, and these enabled the student to take the Licence of Apothecaries Hall. Hospitals existed to help the ‘sick poor’. But what type of sickness should receive treatment and who, precisely, were the poor? The Lancet described a hospital’s functions as to assist ‘suitable cases for charity, supply the wants of the afflicted, and obtain the assistance of eminent advisers with the comfort of adequate provision, whilst they are unable because of sickness or accident to follow their normal pursuits.' 8 Some concepts, generally accepted in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, are hardly understood today. Society distinguished those who were poor from those who were destitute, and likely to remain so. Self-reliance and thrift led some who were poor to make provision for the cost of illness, but the hospitals usually interpreted their role generously so that labourers, small tradesmen and mechanics needing their facilities would be admitted. To extend charity further, to assist those who sought free care but were well able to pay, was considered an ‘abuse’ of the funds contributed by the charitable. Neither was it the province of charity to assist those who should turn to the Poor Law. Charity should prevent destitution. It was the role of the Poor Law to relieve it. Charity was a free gift designed to raise people so that they could support themselves independently once again. Funds were limited and they had to be applied selectively where they would do the most good. Those unlikely to recover rapidly as a result of hospital treatment would inevitably be a burden on the charity, and they were often refused admission. Selection of patients might also be affected by religious or social attitudes. Fallen women, those with venereal disease, or who were suffering as a result of their own dissipation, might be regarded as unfitted for charitable care. If future independence was impossible, and the claimant was likely to remain destitute, charity had little part to play and might indeed be injurious.9 Hospitals were there to admit deserving cases, capable of rapid improvement. Henry Burdett, a well-known hospital administrator, said: "the object of the hospitals is to cure with the smallest number of beds the greatest number of cases in the quickest possible time. the people who are entitled to free relief are those who are able to maintain themselves independently of all extraneous assistance until the hour of sickness when the breadwinner, for instance, is struck down, or the added expense of sickness in the home renders it necessary that the hospital or dispensary should step in.10. The Poor Law system is described in the next section. The organisation of clinical work Until the end of the nineteenth century there was little treatment a hospital could offer which could not be provided just as effectively in a well-appointed domestic dwelling. The better-off, who were ineligible for hospital care, were therefore treated in their own homes. Nevertheless, by the standards of the time the great voluntary hospitals of London provided a high quality of care and according to a French enquiry in the 1860s it was safer to be in a London hospital than one in Paris.11 In 1822 Sir Gilbert Blane listed the commonest conditions in hospital, as opposed to private practice, as intermittent fevers, rheumatism, dropsy and continued fever.12 Chronic tuberculosis, affecting bones and joints, tumours at an advanced stage, bladder calculi and the late results of syphilis were also frequent. Graphic accounts of individual cases can be found in the hospital reports and mirror of hospital practice in The Lancet. From the first issue in 1823, Wakley published detailed accounts of patients under the care of the physicians and surgeons of the metropolitan hospitals. Not only had he personal access to the wards and theatres, but he employed senior students as his reporters. The way clinical work was organised in the three endowed hospitals was described in some detail by the Charity Commissioners in 1840.13 It was customary to admit patients on one day of the week; Tuesday at St Thomas’s, Wednesday at Guy’s and Thursday at St Bartholomew’s. Usually there would be between 50 and 100 applicants each admitting day, but emergencies and accidents would be received at any time. During the first 33 weeks of 1836, 1,725 cases were admitted to St Bartholomew’s on Thursdays, and 1,797 cases as emergencies on other days. Medical staff made a rapid assessment of the clinical priority of those attending, who were well aware that a judgment was also being made on whether they were fit objects of charitable relief. In the endowed hospitals the urgency of the case and its medical interest were the main criteria for admission, but elsewhere a recommendation from a subscriber or a governor’s letter might prove the decisive factor. Once admitted a patient would be bathed and put to bed. A card bearing the patient’s name and that of the medical officer responsible might be fixed to the bed. The doctor would visit the patient and write his prescriptions in the ward book, which would be taken by the sister to the hospital apothecary’s shop for the medicines to be dispensed. When the hospital was full patients would regretfully be turned away to try their luck elsewhere. Until anaesthesia was introduced in 1847 comparatively few operations were performed. Each hospital had a traditional operating day, published in the journals. All the hospital’s surgeons would receive notice of the cases and might attend, crowding the theatre with their dressers and pupils. When ready for discharge, a patient might be asked to visit the Steward’s office and give humble thanks to the charity for his cure. Both the endowed and the voluntary hospitals concentrated on the curable to prevent abuse of their facilities and avoid the risk of their becoming mere almshouses. Some charities framed their rules to exclude specific diseases. Nevertheless, Bristowe and Holmes showed in 1863 that all the great hospitals were admitting typhoid and typhus fever, that smallpox sometimes found its way into the wards, and that syphilis was regularly admitted to the Middlesex, the Royal Free, Guy’s and Bart’s.14 Cancer cases would be taken by the Middlesex. Hospital committees might stipulate how a charity was to be run, but the principles and practice of a hospital did not always coincide. As the capacity to treat disease grew, hospitals became increasingly selective, choosing those who would benefit rapidly, particularly from surgical treatment. Selection was necessary because the number of beds available was restricted by the money which could be raised. The population of London was growing, and the accommodation was unable to meet the needs. Those who required long periods of treatment could not be admitted even if improvement was ultimately probable. The hospital was not a refuge from the buffeting of the outer world, but a great and complicated piece of machinery, every detail of which had as its object the care of the patient.15 Reliable information about the clinical activities of the hospitals was difficult to obtain. The witnesses giving evidence to the Select Committee on Medical Education in 1834 regretted that analyses were not available in the London hospitals as they were in France and Germany.16 Wakley estimated that about 25,000 inpatients were treated each year in the London hospitals, of whom about 2,200 died. How many were investigated and recorded in the hospital records? Wakley quoted a book written in 1732 by Francis Clifton, physician to the Prince of Wales, which suggested that details of cases be kept and published annually. The Lancet believed that numerical methods were necessary for the advancement of medical science. The Statistical Society of London had circulated forms for the hospitals to use, for the accumulation of facts was an obvious duty, and medicine was a science of facts and experience.17 Florence Nightingale supported the cause of better hospital information, read a paper on the method of reporting hospital statistics to the International Statistical Congress in 186018, and designed returns which hospitals might use.19 However only a few hospitals, like Guy’s and University College Hospital, kept good records. Even fewer published systematic analyses of their work, with the mortality of each type of case. With increased interest in medical science some began to do so around the middle of the nineteenth century. St George’s started to publish its figures in The Lancet 20, and roughly at the same time a uniform nomenclature of disease was prepared by William Farr and adopted by the Registrar General. The foundation of a hospital statistical system was laid. As selection of cases for admission became increasingly refined, some needs had to be disregarded. The Lancet said that every hospital physician and surgeon must have suffered many a pang while laying down the rule that hospitals were for the really sick, and not merely wretched; and that curable cases had priority over those which could not expect relief.21 Those working in the hospitals saw the need for additional accommodation for cases which required prolonged care and skilled nursing. Some hospitals therefore developed convalescent homes or country branches, like St George’s which was enabled to do so by a legacy from Mr Atkinson Morley. He had been a student at St George’s and was later the proprietor of the Burlington Hotel in Cork Street. Medical interest rather than social need is too glib a way of expressing the policy of selection. Any other approach would have created its own problems. There are plenty of examples showing that a hospital attempting to meet all needs from foundling children to the infirm elderly soon ceases to provide a service for the acutely ill. The growing importance of the medical schools attached to the great hospitals could only accelerate the trend to selectivity, and the large number of patients who applied for charitable relief inevitably meant that some were more fortunate than others. The voluntary hospitals could not meet all needs. The governorsWith the exception of the endowed hospitals, where other rules applied, the governing body usually consisted of everyone who had made a significant contribution to the funds of the hospital, either on an annual basis or by life subscription. The details varied from hospital to hospital, but usually stemmed from the way in which the institution had been established. Most had been founded by individuals or small groups, and were constituted by Royal Charter, Act of Parliament or by a constitution agreed at a public meeting of subscribers. The governors were not publicly accountable, yet increasingly these privately run institutions came to bear public responsibilities. At St Thomas’s and St Bartholomew’s the treasurer was a senior governor; at Guy’s he was the chief officer. The Lancet said that ‘a passion deeply rooted in the human race is the love of governing’.22 There were extensive opportunities for the energetic subscriber to govern for it was from amongst the governors that the weekly management committee was elected. These committees undertook the regular business of the hospital and met more frequently than the full governing body. Most governors, however, were not energetic and were indifferent to all their privileges, save the right to recommend patients for admission by ‘governors’ letters’. In the competition for subscribers this privilege was widely offered; the initial appeal on behalf of the North London Hospital (University College Hospital) offered three-guinea subscribers the right to recommend three inpatients and six outpatients yearly, four of whom might be pregnant women.23 Thus hospital management tended to pass into the hands of a few people, usually prominent subscribers, sufficiently skilled and with enough time to devote to the charity. Wakley and The Lancet did not approve of inner circles, particularly as medical staff were often excluded from governorship and management. At St Thomas’s and the other endowed hospitals the concentration of power in the hands of the treasurer was great indeed. When management committees met, the individuals present tended to vary. The policy of a hospital might therefore change without warning. Few would entrust their personal affairs to a body never likely to be the same twice in a year, but this was the position in many hospitals. It was hardly surprising that management was sometimes lax.24 The role of the governors inevitably altered as the functions of the hospitals themselves changed. Founded as philanthropic institutions for the sick poor, they rapidly became training schools for doctors and centres of scientific research. The power structure within a hospital which was developing an educational role as well as a ministering mission could be controversial since contributions were usually forthcoming for the care of the sick, not because of the scientific reputation of the institution. Professional eminence alone did not guarantee a hospital financial prosperity - indeed it could be a drawback. Doctors were seldom major subscribers to the charities, although they might give their time free of charge. He who pays the piper calls the tune — and the hospitals depended upon lay support. The wealth and financial security of the voluntary hospitals varied widely. In any year there might be a small surplus or a worrying deficit. The London Hospital had to close wards and streamline administration to meet straitened circumstances at the end of the eighteenth century. The Middlesex Hospital narrowly avoided a strike in 1800 when the staff objected to the shortage of potatoes and the poor quality of the beer following an economy campaign. In 1821 the weekly board was told that more expensive drugs were being dispensed than was proper for a charitable institution, the surgeons were prescribing increasingly and that the use of leeches had risen to almost a hundred a day. As they cost sixteen shillings a hundred it was suggested that each was used twice. A leader in The Lancet pointed to the need for hospitals to combine efficiency with economy and for medical men to assist in keeping hospital expenditure within due bounds. Junior doctors seemed to believe that drugs were cheap and were extravagant in the use of lint and bandages. Their seniors might cut costs by substituting beer for wine and normal diet for eggs and fish when the nature of cases permitted.25 Only the three endowed hospitals had significant reserves. The others were dependent upon the money received year by year, and ran continuous appeals and publicity campaigns. Some financial crises lasted many years; an agricultural depression would affect investments and the ground rents received. Those subscribing might be actuated by pure philanthropy, or a desire for social advancement, but hospital secretaries were concerned with money rather than motivation. Reports and appeals would be written to create in the minds of those who were charitable only in the slightest degree, a flattering illusion of their virtue. Hospitals stressed their individual attributes, the Westminster its position as the as the ‘oldest hospital in London supported by voluntary contributions’; Charing Cross the services it rendered to victims of accidents in the Strand and Covent Garden; and the Seamen’s Hospital its work for merchant seamen of all nations and in the field of tropical medicine. Regular subscribers were courted and subscription lists were invariably published. Desperate advertisements for donations and festival dinners at which the nobility presided and the wealthy attended, provided at best precarious support for hospitals without large endowments. It was easy to ridicule these dinners, for the costs sometimes exceeded the sums apparently raised, but the managers of a charity might use a dinner to focus and impress the features of an appeal, and obtain publicity. As long as hospitals of renown were compelled to beg, anything which brought publicity had to be welcomed or condoned. All were enrolled in the cause of sweet charity. At a charity performance at the Hospital for Sick Children, Great Ormond Street, a well known actress, recalling a notorius highwayman, delivered lines typifying the tone of appeals 26 I crave for them your

sympathy untold, Sometimes those who made only a small contribution at a dinner, later became major benefactors and hospitals had to be persistent to remain in the public eye. 27 The London hospitals were in the centre of the wealthiest city in the world, but unlike the hospitals in provincial towns they were not a focal point of municipal pride. They were in financial competition with each other, a competition which might become bitter when major appeals were launched simultaneously. The numbers of charitable people were as few then as they are today, yet the Corporation of the City of London helped when it could. The Mansion House was often the meeting place for those discussing the problems of the hospitals and raising funds, and the Lord Mayor himself frequently launched appeals. The medical staffing arrangements differed according to the size, the wealth and the prestige of the hospital concerned. At the three endowed hospitals the arrangements were broadly similar.13 There were three principal physicians and three principal surgeons who attended their cases several times a week. The senior medical staff of the great hospitals were generally Fellows of the Royal Colleges of Physicians or Surgeons. If they were not, with few exceptions they soon obtained this distinction. The smaller voluntary hospitals, and the dispensaries, could not be so selective. A salary might be paid to the senior medical staff but it would be small and largely symbolic. A greater reward was to be expected from the fees paid by pupils and dressers. Each surgeon at Guy’s had the right to appoint four dressers) from among the pupils. Dressers were not chosen for their talents or proficiency, ‘but in consideration of an additional fee of £50 for twelve months’.13 At hospitals of less renown than the endowed hospitals the medical staff might be smaller, doctors would not be remunerated for their services and, if there were no medical school, pupils, dressers and house surgeons might not be found. In the absence of the senior staff patients would be looked after by assistant physicians or surgeons, who generally had duties in the outpatient department. The assistants could look forward to promotion with some confidence, for in the words of the Charity Commissioners in 1840: ‘there seems no doubt that the fact of being connected with the establishment forms a very important element in the probability of success of a candidate for one of the three surgical or medical offices of the hospital.’ Open competition as a way of advancement in a profession was rare in the early nineteenth century; competitive examinations were not instituted in the Civil Service until 1870. The Times said that connection with a great hospital was the main ambition of London physicians and surgeons.28 ‘It gives professional status; it brings fees for tuition which are serviceable during the time of waiting for fame; it often leads to a large and lucrative practice; and, indeed, without it there is scarcely a possibility of a very high position being attained.’ The Times considered that men possessing such advantage wished to share them with the smallest possible number of people, and to pass them on to their own kinfolk and friends. The position of apothecary had passed from father to son at both St Thomas’s and Guy’s. Indeed though many brilliant men served the hospitals, the methods of selection were easy to criticise. Generally senior medical and surgical staff were elected by ballot of the governors, a practice which had seemed harmless enough to begin with, for who were better placed to guide a charity than its subscribers? But, as the Charity Commissioners pointed out, few governors had the knowledge to decide upon the relative competency of rival candidates, and it was inevitable that they would look to the existing staff for advice.13 Personal influence rather than achievement was therefore the key to advancement. One treasurer said that the reputation which a post on his staff conferred was worth £5,000. Posts being the doorway to fortune, the profession ‘keenly and not seldom meanly contested the opportunity to give away their skill, time and experience.’ 29 Whilst doctors were so willing to serve a hospital without apparent reward, it was hardly surprising that governors saw no reason to pay them. Posts would be contested as fiercely and as expensively as those in a parliamentary election. Candidates circulated handbills to the governors and might pay for their friends to become governors to add to the votes they would receive. Pupils who had paid the substantial sum to be dresser to a surgeon might in later life look to him to support their candidacy. Under such a system outsiders stood little chance, and inbreeding was the rule in most of the great London hospitals. 30 The relationship between the medical staff and the administration was usually smooth but could be, in the words of The Lancet, ‘fruitful in annoyance and far from conducive to efficiency’. As a rule, the honorary staff were excluded from the governing body. Only at University College Hospital and the Westminster was this not the case - and at St George’s and St Mary’s where doctors were eligible to subscribe and become governors like anyone else. At no London teaching hospital was any of the consultants a member of the weekly management committee. In the three endowed hospitals exclusion was based on the principle that the management of the hospitals’ princely revenues required specialised knowledge and ample time, qualities not often found amongst eminent medical men.22 The claim for greater medical influence was frequently pressed in medical journals like The Lancet and it became a matter of open controversy from time to time, as it did at St Thomas’s in the 1860s, Guy’s in the 1880s and the National Hospital for the Paralysed and Epileptic at the turn of the century. In the earlier part of his career one of the great figures in the Victorian hospital world, Henry Burdett, supported the demand of medical staff for board membership. Later he came to prefer the approach adopted at St Thomas’s, The London, the Middlesex and other great hospitals, which operated ‘peacefully and satisfactorily’. At these hospitals it was recognised that the medical staff had a purely professional role and there was a medical committee to which the board referred matters of hospital management with professional implications. The alternatives were for two of the medical staff, elected by their colleagues, to serve on the board or, rarely, for the whole of the medical staff to be ex-officio members. 10, 31 The medical press objected to suggestions that doctors who gave their time to a charity free of charge should be regarded as no more than employees of the governors. Doctors would certainly have preferred a medical presence on their board, but usually they only became outspoken when they found themselves unable to influence the governors. This was the position at the National Hospital for the Paralysed and Epileptic, where the staff felt that although it was their skill which had established the hospital’s reputation, their views would only reach the board if Mr Burford Rawlings, the secretary-director, was prepared to pass them on. After thirty two years of service the board seldom overruled ‘so splendid a specimen of hospital officialdom’, as he was described by Burdett. In Burford Rawlings’ view, doctors found it difficult to balance the needs of their patients against purely scientific and professional considerations. He therefore felt that doctors should be excluded from governing bodies, that the lay administrators should have wide powers, and be accountable to the board for their use. After a battle lasting many months the doctors gained representation on the board and Burford Rawlings resigned to make way for a hospital secretary prepared to accept a professional presence on the Board. 27, 31 It is traditional to be critical of the standard of nursing care in the earlier part of the nineteenth century, but whilst the medical journals seldom commented upon it, the London voluntary hospitals enjoyed the reputation of providing ‘the best that the knowledge and the practice of the times permitted.‘ 31 The report of the Charity Commissioners on nursing at St Thomas’s in 1836 makes it clear that in some hospitals at least it was disciplined and responsible and that Sairey Gamp would not have lasted for long. The ward sisters, as the principal nurses in immediate personal attendance on patients, played the key role. As they were responsible to the matron and the steward for everything within the ward which was not a matter for the medical staff, the selection of a new sister received great attention. Usually women were recruited who had received some education and had lived in a respectable rank in life: perhaps widows in reduced circumstances, head servants, housekeepers or head nurses in gentlemen’s families. The sisters required ‘much good sense, zeal and bodily activity’ and the necessary practical skill and experience were only fully attained after long service.13 St Thomas’s preferred to have a relief sister in training so that an unexpected vacancy could be filled by a woman already tested for a position on which ‘so much happiness and misery depended’. Once appointed, sisters usually retained their post for life. Nurses were seldom promoted, as they generally came from a lower social class. Nurses were appointed by matrons who tried to find women of good character. In 1845 the matron of the Middlesex told the weekly board how she chose nurses. They should be between 30 and 45 years of age, strong, healthy, unmarried and unencumbered with children. They should be accustomed to nursing, able to read and write, humane, honest, sober and clean in their work and person. They should be neither stupid nor conceited, good tempered and able to bear with those who were not, but who nevertheless needed to be nursed. The nurse had to be firm in seeing that the rules in the ward were complied with, yet gentle in her manner of enforcing them.13 Pay being low, recruitment might be difficult and from time to time it was necessary to discharge nurses for taking bribes, drunkenness or rollicking with the patients. By day the nurses performed domestic duties and administered to the wants of the patients. At night ‘watchers’ of a yet lower class supervised the wards, calling the sister who slept nearby if there was an important change in the condition of a patient. If watchers lay down or slept they were instantly discharged. The theoretical basis of nursing practice being slender, nurses inevitably learned their craft in a practical way. Catholic nursing orders had long selected their probationers on a vocational basis, and the protestant deaconesses at Kaiserswerth, near Dusseldorf, were also chosen in this way. Kaiserswerth, where Florence Nightingale spent a short time, was something of a model for the Protestant Sisters of Charity organised by Elizabeth Fry. This order trained nurses for private work, but they and succeeding orders gained experience in hospital wards at Guy’s, St Thomas’s, the Middlesex and other London hospitals. St John’s House and Sisterhood, founded in 1848 as the first purely nursing order of the Church of England, was more significant for London’s hospitals. Louisa Twining credited the order with beginning the reform of nursing.33 The order introduced a system of promotion for nurses of proven competence, instruction being provided on the wards of the Westminster and the Middlesex hospitals. Its training school was a comparatively small affair and in 1856 it numbered 19 sisters, 27 nurses and 10 probationers.34 St John’s House provided the model for a number of other sisterhoods, many High Church in outlook, and offered a new way of staffing hospitals and improving the standard of nursing care. In spite of the opposition of some members of the medical staff and the hospital management committee, St. John’s House was asked in 1856 to provide the nursing service at King’s College Hospital for a fixed sum per year. The Order’s first reform was the introduction of ‘scrubbers’ to relieve the nurses of household drudgery. Next came the abolition of the notion that night nurses were an inferior order by rotating day and night staff. Then followed the proper care of the nurses’ health by the provision of well cooked meals in a common dining hall.35 A simple but sensible pamphlet was given to the nurses on the need for careful observation of the patient, obedience to medical instructions and the desirability of keeping good records. The nurses of the Sisterhood, clad in their dark woollen robes, were under the instructions of the medical officers, but remained members of the religious body. They reported to their own female head, a system of which Miss Nightingale approved, and were not servants of the hospital committee or under the orders of the hospital secretary.19, 36 From 1866 St John’s House also provided the nursing for Charing Cross Hospital. The Order of All Saints, which had extreme High Church tendencies, took charge of the nursing at University College Hospital in 1862 after a trial period. The lady superintendent at University College Hospital had previously been a sister at King’s, and when she took over the standards of cleanliness and order improved, just as had been the case in the Strand. Voices were frequently raised against the nursing being ‘farmed out’ in this way, sometimes because of the division of authority within the hospital, sometimes because it was alleged that sisterhoods were less concerned with nursing standards than with the Christian frame of mind in which patients died. Sectarianism might also cause dissension because it could affect the selection of probationers. A High Church woman would probably apply to King’s College Hospital, or to University College Hospital where the All Saints’ Sisterhood would only accept members of the Church of England. A Catholic or Dissenter might choose to go to The London, the most unsectarian of the hospitals, which had declared itself firmly against nursing by sisterhood.37 When a physician or surgeon needed a nurse to look after a private patient at home he would turn to his own hospital or to a nursing sisterhood. In 1872 Kelly' Medical Guide listed eight nursing institutions ‘from which skilled and properly trained nurses and attendants could be obtained’, including St. John’s House and Sisterhood.38 The provision of nurses for private patients produced a steady income for the sisterhoods and enabled nurses to obtain employment at a rate higher than the hospitals themselves would pay. The sisterhoods would also supply staff for dangerous and unpleasant duties. During epidemics they would assist the hospitals, supplying nurses to help as the wards became filled with cases of smallpox and cholera. Hospital ‘healthiness’ and hospital design The cause of fevers and septic diseases in hospitals was debated for much of the nineteenth century. Where they the result of foul air, stagnant putrefaction, bad drainage and overcrowding? How important was it to separate the sick from the healthy? Was it dangerous to aggregate epidemic cases in large hospitals? And later, after the work of Louis Pasteur and Lister, how far was the germ theory of disease valid? These disputes divided those interested in hospitals into warring factions, for the rival theories affected the way in which hospitals were designed, located and organised. A belief in miasmata, unhealthy influences saturating the atmosphere and penetrating the structure of buildings, underlay many of the principles of hospital construction. In the early years of the century London hospitals performed their duties fairly well as long as they were occupied mainly by chronic medical cases and were not overcrowded. Under conditions of stress their performance deteriorated. The building of railways in the vicinity led to the admission of many accident cases and often to a rise in the sepsis rate. ‘Hospitalism’, as it was called, became an inevitable if spasmodic feature of the wards, with pyaemia, erysipelas and gangrene complicating otherwise successful surgery. The mortality rate of different hospitals was compared, although Sir Gilbert Blane had pointed out as early as 1822 that such tests were unreliable unless the severity of the cases admitted was taken into consideration. A high death rate might merely mean that the selection of cases had been judicious.12 ‘Hospitalism’ might also have been exacerbated by the rapid increase in the number of operations carried out after the introduction of anesthaesia in 1846, which increased the pressure on the wards, straining buildings designed for a less active style of medicine. 15, 39 The inevitability of hospital sepsis came to be questioned, and the principles of hospital siting and design were examined. Better architects had considered such matters for many years; when the Westminster Hospital was rebuilt in Broad Sanctuary in 1832 the architect, Mr Inwood, who had designed the Coliseum and St Pancras Church, ‘contrived to afford unstinted supplies of natural light and ventilation’. Each patient was allowed 1,900 cubic feet. More often, however, architects called upon to design a hospital or infirmary would apply their experience of domestic architecture uncritically. Buildings would be erected with handsome frontages, often in the form of Grecian temples with elaborate porticos, behind which the wards would be crowded together. Continental practice was studied assiduously. The new hospitals in France at Lariboisière and Vincennes, which were built on the pavilion principle, were considered greatly superior to the new military hospital at Netley, on Southampton Water.40, 41 In 1856 Florence Nightingale met William Farr; both were close associates of Edwin Chadwick. Farr and Nightingale collaborated in campaigns for sanitary reform and in 1858 Miss Nightingale presented papers on the principles of hospital construction to the Social Science Association. The papers brought together the features of the hospital design which the sanitarians considered to be of importance and they were reprinted as Notes on Hospitals.42 ‘The first requirement in a hospital’, she wrote, ‘is that it should do the sick no harm.' Miss Nightingale, Dr Southwood Smith and many of the sanitarians underestimated or discounted the possibility of contagion and believed that the cause of slow recovery of patients, the high mortality rates of the hospitals, and hospital fever, were the results of air-born miasma caused by overcrowding. Florence Nightingale therefore stressed the need for natural ventilation, and objected to ‘agglomerating a large number of sick under one roof.' She also disapproved of town-centre locations, saying that in a hundred years’ time it would be considered impossible to put the sick down in the middle of a crowded city.43 ‘If the recovery of the sick is to be the object of hospitals they will not be built in towns. If medical schools are the object, surely it is more instructive for students to watch the recovery from, rather than the lingering in sickness. Land in towns is too expensive to secure the conditions of ventilation and light, and of spreading the inmates over a large surface area instead of piling them up three or four stories high.’ 42 Dr Stone, medical registrar to St Thomas’s, was one of a number of doctors who rebutted the criticisms levelled at the existing hospitals located in the centre of town. He pointed out that the hospitals with comparatively few beds selected the acute, the critical and the moribund. The hospital in the greatest demand had the highest death rate; the more foul its contents the more efficiently it was doing its duty.44 John Simon, [1816—1904 Lecturer in pathology and surgeon to St Thomas’s, first Medical Officer to the Corporation of the City of London and to the Privy Council] was keenly interested in the variations in death rates. Comparatively few of the studies which he commissioned bore directly on hospital care, but in 1863 he asked the Lords of the Privy Council to commission an investigation into the sanitary conditions of hospitals. He appointed Dr Bristowe, physician to St Thomas’s, and Mr Holmes, assistant surgeon to St George’s, to undertake the study. They spent a year visiting 103 hospitals in the United Kingdom and 15 in Paris. Their report included the ground plans of the hospitals they visited, details of the admission policies, the diagnoses of the patients on the day of the visit, the problems of sepsis and, where possible, the clinical activities of the hospital. They discussed the influence of construction upon mortality, the causes of ‘unhealthiness’, the advantages of town and country locations, how fever cases should be distributed within a hospital and the importance of accurate records. The report was 281 pages long, and The Lancet considered it so important that it serialised a précis.14 Bristowe and Holmes considered that case selection was the dominant factor affecting the death rate of a hospital. The mortality of surgical cases was lower than medical ones, so that the proportion within each hospital was important. The demand for treatment also influenced the mortality rate because a hospital under stress admitted those who were most seriously ill. Large city hospitals admitted graver conditions than small country ones, which had fewer demands upon them and were more like almshouses. The system of governors’ letters and the restriction of admissions to certain days of the week also tended to exclude emergencies and those who were gravely ill, to such an extent that some hospitals were largely filled with the protégés of the subscribers. Bristowe and Holmes classified the basic designs of hospitals and tried to relate ‘healthiness’ to the pattern of construction. The pavilion plan with its entirely separate blocks was costly to construct, required much space, and the distances between departments were considerable. Nevertheless the blocks were well ventilated from all sides and the plan was probably ideal from the sanitary point of view. Corridor-hospitals, in which the wards were connected by corridors off which they opened, resembled the pavilion hospitals, the pavilions being regularly arranged along a spine corridor. They might be several stories high, but if the wards were large, the corridors well ventilated and the spacing between the blocks wide, they were satisfactory. H-shaped hospitals, with the wards in the side limbs, built around a pattern of corridors, had much to commend them, but were difficult to extend. Because Bristowe and Holmes did not accept that the location and sanitary state of a hospital were the main factors determining its mortality rate, they were attacked by Farr and Nightingale who produced statistical evidence in favour of the sanitary case.45 Tables Farr produced for the report of the Registrar General in 1864 (see below) presented the death rates in hospitals differing in size and location. Farr expressed mortality as the number of deaths in a year compared with the average bed occupancy, so that in effect he did not distinguish between 12 patients each occupying a bed for a month, and one patient in hospital for a year. A hospital with an average bed occupancy of a hundred in which, during a year, there were two hundred deaths therefore had a mortality rate of 200 per cent. It appeared from Farr’s figures that the mortality of the sick who were treated in large hospitals in large towns was double the figure for small hospitals in country towns. Farr’s figures were used by Florence Nightingale who said that while there was difficulty in comparing hospitals because of the different proportions of serious cases, the aggregated mortality rates were reliable evidence that the most unhealthy hospitals were those of the metropolis.

The Lancet, reviewing the 1863 edition of Notes on Hospitals, said that inadequate attention was paid to the different types of cases admitted, and a comparison of the outcome of similar clinical conditions treated in different types of hospitals was needed. Holmes accused Farr in The Lancet of devising an erroneous method which led to absurd conclusions and said that ‘in so far as the method was original, for medical purposes it was untrustworthy’.46 Maintaining that the sanitary state of a hospital was one of the lesser factors affecting a hospital’s death rate, he drew attention to the effect of the presence of a medical school, as it led the hospital to collect a disproportionate number of grave cases, often referred from a distance. The debate on the healthiness of town and country sites, and of patients treated in private and hospital practice, rumbled on for many years. Sir James Simpson and Timothy Holmes spoke about it at the British Medical Association meeting in 1869 and wrote at length in The Lancet. The Times also commented on the differences between hospitals. Some might be ‘half-full of superannuated coachmen or hysterical housemaids, whilst the poor languished in mortal sickness in adjacent streets.’ 28 The controversy had little effect on the distribution of hospitals in London. Those which were later relocated did not move to the country, but to busy parts of town. Doctors became more interested in the mortality of particular diseases, treated by different methods in different hospitals. Though antiseptic procedures were slow to be adopted in London hospitals, they seemed to offer a more direct way of reducing mortality. Holmes always lamented the ‘exaggerated importance’ attributed in the writings of Miss Nightingale and the sanitarians to the details of hospital construction and ventilation, when in his view little improvement was needed to most of the London hospitals. 47 The subdivision of medicine into specialties, taken for granted today, was a mid-nineteenth century development. Concentration on fields narrower than general medicine or general surgery met with resistance within the great general hospitals. Specialisation ‘narrowed the mind’ and led doctors to diagnose their favourite condition in every patient they saw. Even worse, some members of the medical profession viewed specialisation as an attempt on the part of a young doctor to advertise his talents. The ideal doctor was the man like Jonathan Hutchinson who was at the same time a superb general physician and master of specialties. The failure of the general hospitals to find room for doctors who were sometimes the best in their line was partly the reason for the emergence of special hospitals. The medical schools, said The Times, ‘are constantly sending forth men who are conscious of powers above the average, and who are ambitious of a fitting arena for their display. To some fertile brain the idea of the first “small” hospital must have occurred ... and the hospital is usually not only small but “special”. An ambitious man who does not see his way to any existing hospital will found one of his own.’ The first special hospitals to be established were lying-in hospitals, hospitals for fevers, for venereal disease and for the eyes.48 Sometimes special hospitals developed from a dispensary to which inpatient accommodation was added. A few provided services to particular groups of patients - Italians, French, seamen, or women and children. Others only dealt with particular illnesses or organs, like the Lock Hospital, founded in 1746 to provide the West End with facilities for the treatment of venereal disease. Some were founded for purely charitable reasons, as was the National Hospital for the Paralysed and Epileptic. Certain groups of patients, like consumptives and children, were seldom received by the general hospitals, and the dispensaries, special hospitals and workhouses filled the gap. With the exception of a single ward at Guy’s, one might walk the wards of every hospital in London in 1850 without seeing a single case of disease in childhood.49 But most special hospitals owed their origin to the quest for professional advancement of a new breed of doctor - the specialist. The usual. procedure to found a special hospital was to form a committee, obtain an eminent patron, take a house, appoint medical staff and launch an appeal. Advertisements for funds would appear in the press pointing out how appallingly deficient was the care for certain diseases, but that now as a result of the benevolence of disinterested and far-seeing men the lack might be remedied.50 As the population rose, a large number of the special hospitals were established, as private hospitals are today, in the area which is now the City of Westminster. Counting their number was difficult, for many were ephemeral. Kershaw made the attempt, and his figures demonstrate heyday of special hospital development.48

The size and wealth of London provided an opportunity for the development of specialism and specialist hospitals which did not exist to the same extent in the provinces. The professional rewards could be considerable but jealousy was ever present. Only occasionally was support from colleagues forthcoming, as it was when the medical staff at St Thomas’s and Guy’s supported the establishment of the London Dispensary for the Eye - now Moorfields - by an ex-colleague. The management committees of general hospitals tended to be suspicious of specialist care and it was often the staff of the special hospitals who were responsible for advances in diagnosis and treatment. General hospitals would wait a few decades until a new field of work was well established before providing beds and opening their own department. When a general hospital did so, the doctor appointed might merely be the newest member of the staff, whether or not he had previous experience in the field. Such men might be given little authority and might even be denied the right to operate on their own patients.51, 52 Service and teaching inevitably suffered and research into new methods of therapy was handicapped. Scientific advance might be easier in the special hospitals, where conditions might be admitted which were rejected by the general hospitals. Consumptives, for example, had a poor prognosis and a long length-of-stay and were seldom admitted to general hospitals. The Hospital for Consumption was established to meet their needs, and the first report from the Brompton was of such excellence that The Lancet said that it placed the hospital in the first rank amongst the useful medical charities of England.53 The medical press and the special hospitals The medical press had little time for the special hospitals. The Lancet wrote: .... if a stranger were to peruse the list of our London medical charities, commencing with the magnificent endowed hospitals, and going through the tedious list of dispensaries and special institutions, his first impression might possibly be one of admiration at the apparently boundless philanthropy of the British public. He could not account for their multitude and variety otherwise than by concluding that charitable beneficence is actually a passion so absorbing and insatiable, that it is ever keenly on the alert to discover new objects on which it can be exercised. The eye, the ear, the bones and tendons, the heart and lungs, the rectum, the uterus, the skin, women and children, are all specially provided for. Many individual diseases besides, as cancer, consumption, fistula, syphilis, sore legs, supposed to be of too recondite pathology for the general hospital physician, form special objects of treatment in distinct institutions. Division and subdivision in medicine having been carried so far that there is nothing left to divide, the rage for curing everybody for nothing is necessarily expended in multiplying institutions of the same kind.' 54 There was no doubt that some special hospitals were mainly concerned with marketing the skills of their staff. Bristowe and Holmes wrote that ‘it is not want of charity to say of most special hospitals that they are founded to serve private ends and neither have nor were intended to have any beneficial effect on the public health’. There were also medical problems. The mortality rate of maternity and children's hospitals could be horrific.55 Only by closing the hospital down for some months could some epidemics of sepsis be controlled, and it might be asked if such hospitals did not do more harm than good. Nevertheless special hospitals would not have multiplied as they did if they had not met a genuine need. They probably provided a milieu in which a new activity could flourish. For example, Spencer Wells, at the Samaritan Hospital, demonstrated that with careful technique, ovariotomy could be performed with an acceptable mortality at a time when the general hospitals discouraged such operations. The Lancet was not mealy mouthed in its condemnation. ‘There are public injuries which cannot be justified by private necessities; and among these must be classed the multiplication of special institutions in this metropolis ... These excrescencies are being reproduced with all the prolific exuberance characteristic of malignancy and soon the metropolis threatens to swarm with nuisances of this kind.’ The Lancet said that amongst the worst was a hospital founded to provide a special form of treatment already available in the general hospitals. ‘This institution is denominated the Galvanic Hospital ... next may come a Quinine Hospital, a Hospital for Treatment by Cod-liver Oil, by the Hypophosphites or by the Excrement of Boa-Constrictors.’ The Hospital for Stone, the Dispensary for Ulcerated Legs and the Dispensary for Diseases of the Throat and Loss of Voice had been founded, in the opinion of The Lancet, by doctors unmindful of the good opinion of their colleagues, who had deviated into ‘ultra-special paths over which blows the blast of professional reprobation’. Their medical staff should refuse to be associated with such hospitals and resign.56The Galvanic Hospital and the Dispensary for Leg Ulcers replied to the attack that if the teaching hospitals would establish effective galvanic wards or agree to admit chronic leg ulcers there would be no need for their establishments. The best argument for special hospitals was that some diseases were inadequately catered for and the special hospital could bring similar cases together for study. The special hospital then formed a centre from which knowledge could spread. ‘Classification we must have’, said Jonathan Hutchinson of The London Hospital, ‘for the good of the patient, the better advance of science, and the convenience of both teacher and learner’.57 However, it was argued that administrative costs were increased and charitable money was wasted by multiplying hospitals, and that by collecting together all the cases of a single disease they deprived the medical schools of the material they needed for teaching. Students therefore might be poorly trained.58 The Medical Times and Gazette, The Times and The Lancet said that the solution was in the hands of the general hospitals. They must develop good special departments themselves, group patients with particular diseases together, and keep young men of talent and energy within the general hospitals to develop these specialties. Then special hospitals would disappear. The Lancet examined how far this had happened in a survey in 1869. Most of the general hospitals had established outpatient clinics for skins, eyes, and ear, nose and throat diseases, but only for diseases of women and ophthalmology had inpatient departments been created and these were rather small.59, 60, 61 The rapid development of special hospitals owed much to the energy and inventiveness of their secretaries, who were often highly effective fund-raisers, even if it sometimes seemed that the money raised merely paid for more fund-raising activities.62 In 1875 the 36 special hospitals in London raised between them almost as much as the eight voluntary hospitals with medical schools which were largely dependent on public subscription.63 The special hospitals also received substantial sums from the Hospital Sunday Fund, when that was established, although The Lancet felt that they had no claim on the public purse and that the money should go to special departments of general hospitals instead. Unlike the general hospitals, the special hospitals frequently charged their patients, receiving more from this source than from regular subscriptions. They were therefore in competition with both the general hospitals and with general practitioners. Patients who clearly could not pay might be exempted, but most special hospitals expected a contribution towards the cost of care unless the patient had a governor’s letter of recommendation. As the special hospitals were small, their management costs were high; and because they equipped their staff with the latest in technology, like instruments illuminated by electricity, they had high case costs. Some special hospitals were transient, like the London Galvanic Hospital and the ‘massage hospitals’ which were little more than brothels. The British Medical Journal investigated them in 1894; the treatment was almost always left in the hands of young ladies whose attractive qualities were deftly indicated in various ways and were described by their pet names as 'nurse Dolly or 'nurse Kitty'" A few amalgamated with each other, but many thrived, moving to larger premises and developing medical schools open to undergraduate and postgraduate students.58 Specialists might have a foot in both camps, the special department of a general hospital and an appropriate special hospital. Yet rivalry between special and general hospitals was a feature of the London medical scene. Sometimes a distinction was drawn between the larger special hospitals, with an international reputation, and the smaller ones, but as a group the special hospitals were never free of a feeling of being under siege. The Select Committee of the House of Lords in 1892 deprecated ‘the establishment of small special hospitals where they were not wanted, the waste of money in badly managed small institutions, and work carried out in incommodious buildings under unsanitary conditions.’65 Their Lordships thought that there should be more cooperation between special and general hospitals and subsequent reports frequently contained statements about the desirability of amalgamating special and general hospitals. Inevitably such statements placed the special hospitals on the defensive. The achievement of the voluntary hospitals The voluntary hospital system, which encompassed the great endowed hospitals, the general and the special hospitals, was a massive monument to the concern of the wealthier members of society for the poor in time of sickness. There was pride in the London hospitals for nowhere else did there exist a service so extensive or of such quality. The hospitals had the support of the churches, the patronage of the nobility, and their activities were a central part of the London social scene. Looking at what had been accomplished the philanthropist could be excused a certain degree of self-satisfaction. From the point of view of the patient matters were not so satisfactory. When one considered what was required and examined what was being supplied, the record ceased to be as imposing as the charitable liked to believe. Comparatively few of those needing hospital attention could find a place in the voluntary hospitals, for money was short and beds were in demand. Many who might have been eligible for admission were incapable of doing the rounds of the subscribers in the hope of obtaining a letter of recommendation. To present oneself at a hospital without a letter meant running the gauntlet of the beadles and the porters who had a reputation for brusqueness, but who were not always above taking bribes. Admission was far from assured. Charitable care was better than the poor law, if one could get it, but it was no bed of roses. Charity was incapable of meeting the demands.

|