|

.....there is nothing more

difficult to arrange, more doubtful of success, and more

dangerous to carry through than initiating changes ... The

innovator makes enemies of all those who prospered under the old

order, and only lukewarm support is forthcoming from those who

would prosper under the new. Their support is lukewarm partly

from fear of their adversaries . . . and partly because men are

generally incredulous, never really trusting to new things

unless they have tested them by experience.

Machiavelli, II

Principe 1

The

nature and outcome of the 1974 reorganisation of the National

Health Service can only be touched upon briefly here. It was

planned by a Conservative administration as part of the

government’s wider programme of administrative reform, which

aimed to make it easier to plan and develop services across

authority boundaries and to give scope for changing the balance

of resource allocation between them. Just before the date of

reorganisation a general election brought Labour to power. Mrs

Barbara Castle became Secretary of State for Social Services in

March 1974 and Dr David Owen, Minister of State for Health. Some

features of the reorganisation did not appeal to the new

administration but the central aim of unifying community and

hospital services was accepted as sound.

Reorganisation had a number of objectives. First was the

unification of the three parts of the NHS, hospital services,

family practitioner services and the health services provided by

local authorities, into a single structure. Second, the new

structure was expected to make easier a ‘clear definition and

allocation of responsibilities, with maximum delegation

downwards matched by accountability upwards’. Third, there was

to be a comprehensive planning system to ensure that policies

were translated into action.2 Though the

changes in 1974 can now be viewed as no more than a single stage

in the evolution of the health service system, it seemed a vast

step to those working in London hospitals. With the exception of

the postgraduates, the teaching hospitals lost their boards of

governors, and hospital management committees disappeared. Newly

created area health authorities and health districts served a

defined population. They advertised for staff and many familiar

faces disappeared from the hospitals, either by success in the

competition for the new jobs or by early retirement.

The

‘Grey Book’ on management arrangements for the reorganised

health service was the outcome of a study supervised by a

committee whose members were drawn from the three branches of

the service and the Department, chaired by its permanent

secretary, with the assistance of McKinsey and Co and the Health

Services Organisation Research Unit of Brunel University.3 Roles

and responsibilities were defined with a precision not to

everybody’s liking. The concept of management by consensus among

chief officers of different disciplines was introduced. With

few exceptions the officers of the regional health authorities

were those of the old regional hospital boards; they had many

new things to learn. Health authorities now had a wider span of

responsibilities, ranging from community health services to the

regional specialties and the high technology of teaching

hospitals. Authority meetings were now to be held in public and

the membership of area health authorities included four nominees

of local authorities. Each health district related to a new

consumer organisation, the community health council, which had a

right to be consulted on changes in service and to oppose

significant alterations at ministerial level.

These organisational changes were carried out against a

background of increasing stringency and the new structure was

sometimes blamed for problems which were really caused by a

shortage of money, particularly in London. There was widespread

if spasmodic industrial action by many groups of staff. The

teaching hospitals had difficulty in adjusting to the new order,

and regretted the now distant relationships with the Department

of Health and Social Security. Two were in the process of

relocation, Charing Cross in Fulham and the Royal Free in

Hampstead. Neither believed that the cost of running the new and

larger facilities had been estimated correctly.

Medicine was not standing still. Diagnostic imaging was being

revolutionised, ultrasound was developing and the first computer

assisted scanners were being introduced into London hospitals.

New methods of treatment were developed, often pioneered in the

teaching hospitals but sometimes being introduced into the

practice of district general hospitals. Coronary artery surgery

and pacemaker insertion was expanding rapidly; oncology, bone

marrow transplantation and joint replacement also had to find

their place amongst the services offered, and had to be

financed. Services for the elderly, the mentally ill and

mentally handicapped also needed improvement. These ‘Cinderella

services’ were now unambiguously the responsibility of the same

district authorities as were the teaching hospitals. They

therefore came into direct conflict with new initiatives in

acute treatment, within the same budget.

Planning and

finance

The

introduction of a comprehensive planning system involving the

Department of Health, the regions, the areas and the districts,

was intended to be an essential component of the 1974

reorganisation. Nowhere was it more important than in London

with its legacy of problems. The deficiencies in primary care

and long stay services, the concentration on acute services, and

the problem of reconciling London’s role in medical education

with the level of acute facilities likely to be available in the

future remained unresolved.

The ‘Grey Book’ outlined the nature

of the health service planning system and a few regions like

North East Thames implemented it. Two years after

reorganisation, in 1976, a guide to the NHS

Planning System and a consultative document on Priorities

for Health and Personal Social Services in England were

issued to launch it more widely.4 Planning

was now to be based upon the requirements of different ‘client’

groups, rather than proposals for capital developments at

individual hospitals. It was also to take place within realistic

resource assumptions. Here was a problem; the then current

proposals for building far exceeded the funds likely to be

available. Costs had often escalated and the new regional health

authorities had the unhappy task of informing some hospitals

that long-cherished developments were unlikely to come to

fruition for many years to come.

In London even existing services

were under threat. From 1977/8 regional authorities received

allocations which reflected the decision to re-distribute

revenue in line with the recommendations of the Resource

Allocation Working Party (RAWP).5 This

proposed that the money available to a region should primarily

reflect the size of its population, weighted by standardised

mortality ratios and other factors, rather than the costs of

services currently provided or its historic funding. On this

basis the discrepancies between regional allocations were

considerable. Target allocations, the money which a region would

receive if equity ruled, were calculated. The four Thames

regions were considerably ‘over-target’ and their financial

growth rate would now be below national average. Simultaneously

the Thames regions were expected to redress their own internal

inequalities and deficiencies in service. Some areas were far

better funded than others and hospitals like The London realised

that they would have to lose money to Essex, or to groups like

the mentally ill whose conditions required urgent improvement.

The compounding effects of national and regional reallocation

and the demands of the long stay specialties made the financial

position of the allegedly over-funded central London teaching

districts, and the continuing development of high technology

medicine, look bleak. The University of London and its medical

schools rapidly appreciated the

potential effect upon acute hospital services and medical

education, and established a working party to look at the

position.

The financial pressures upon

teaching districts were now clear but the speed with which they

could react was reduced by the need for public consultation, and

local opposition to any reduction in health services. Some of

the districts with the greatest financial problems were matched

by local authorities which were left-wing in complexion. Their

nominees on the area health authorities made it clear that any

reductions were anathema to them. One teaching area, Lambeth,

Southwark and Lewisham, passed a resolution in 1979 that in

effect limited the extent to which it was prepared to cut

clinical services. This action would inevitably have led the

authority to exceed the cash limit it received. Mr Patrick

Jenkin, the Secretary of State, appointed commissioners under

section 86 of the NHS Act 1977, which permitted him to give

directions for a specific period to ensure, in an emergency,

that services would continue to be available. This decision was

subsequently challenged successfully, but not before a measure

of financial control had been re-established. The court ruled

that Mr Jenkin had acted outside the power of the section by

failing to specify the duration of the crisis. Instead, the

court said, he might have acted under section 17, directing the

authority to economise in specific terms.6

Planning in

London

The

forty years preceding the 1974 reorganisation had seen major

demographic changes and the removal and rehousing of many

Londoners in new towns as an act of policy. The population of

inner London had fallen, faster indeed than the planners had

expected, from 4,397,000 in 1931 to 2,772,000 in 1971. The

number of acute hospital beds in central London had fallen

somewhat, but the proportion compared with the residential

population had risen.

When the figures from the joint survey carried out in 1931 by

the Voluntary Hospitals Committee and the London County Council7 are

compared with hospital statistics for the same listed hospitals

in 1973 (where they were still in operation) the number of beds

in teaching hospitals has risen, mainly as result of post-war

reconstruction at a larger size. Beds in specialist hospitals

fell, largely because small hospitals for women and children had

closed or been incorporated into general teaching hospitals. The

capacity of the old municipal hospitals had fallen partly as a

result of war damage and partly because some very large

hospitals were reduced in size, while some fever hospitals like

the Brook in Woolwich and the Grove in Tooting had been

converted into general hospitals or specialist units. Patients

with acute illnesses were well served, but the position of the

elderly and the mentally ill was less favourable.

Services for these long stay patients were generally provided in

old buildings, sometimes miles from where they had lived. The

changing demography of London called for a different and leaner

pattern of hospital service in central London, although the

process of slimming down was complicated by the need to provide

clinical facilities for the progressively expanding medical

student intake.

Acute beds

available in the same hospitals in 1931 and 1971

| |

1931 |

1971 |

% change |

| Teaching

hospitals |

5,672 |

7,260 |

+ 36 |

| Special(ist)

hospitals |

5,617 |

4,887 |

-13 |

| General,

below 100 beds |

442 |

445 |

+ 0.7 |

| General,

above 100 beds |

2,330 |

2,561 |

+ 10 |

| |

14,151 |

15,153 |

|

| LCC

hospitals appropriated |

16,920 |

9,536* |

- 38 |

| |

31,071 |

24,689 |

- 20 |

| |

7.06/1000

resident population. |

8.9/1000

resident population |

|

*To this figure

one might add beds in hospitals which provided fever services in

1931, but had become general hospitals in 1973. It is impossible

to estimate the proportions of elderly/long stay patients in

hospitals which were, in the main, acute hospitals.

The London Coordinating Committee

The London Coordinating Committee was established in 1975 to

assist in the solution of these problems. There were long

discussions about how, while remaining an advisory body, it

might be given more bite than Dame Albertine Winner’s joint

working party, which had been active from 1967-72. Its terms of

reference were to ‘coordinate the provision of health services

in Greater London with reference to the matching of medical

education and service need and securing rational distribution of

specialised health services’. The Permanent Secretary, Sir

Philip Rogers, chaired the first meeting. Members were drawn

from the regional health authorities, teaching areas,

postgraduate hospitals, the London Boroughs Association, the

Greater London Council, family practitioner committees, the

University Grants Committee, the University of London and the

Department of Health. It proved to be too large and unwieldy a

body: while it provided a forum for discussion it had neither

the capacity nor the authority to take decisions. It identified

a number of local problems requiring urgent solution. Previous

assessments of regional specialties like neurosurgery and

cardiothoracic surgery were brought up to date and the committee

considered a possible strategy for the rationalisation of inner

London hospitals which had been drawn up by Departmental

officers. The tentative proposals included a suggestion that

some recently completed hospital developments should not be

used for the purpose for which they had been designed, but for

other clinical requirements. The document was leaked in the Sunday

Times creating concern amongst the staff of

some prestigious hospitals.8 The

Minister decided to make the document more widely available in

an attempt to allay anxieties.

Meanwhile

regional authorities, unimpressed by the potential of the London

Coordinating Committee, were coming to believe that their own

planning activities might provide more substantial and

achievable economies. The committee gradually lost favour and

held its last meeting in July 1976. For some time afterwards the

members received briefing about London developments, but few

regretted the committee’s passing. Its ineffectiveness

highlighted the problem of developing London-wide strategies

which would achieve general acceptance. Yet the planning of the

Thames regions was proceeding at widely differing rates, and it

was clear that there would be a variation in comprehensiveness

and quality. Nor would the four plans necessarily be compatible

with each other. Elsewhere in the country this might not have

mattered, but in London, where major reductions in services were

likely to prove necessary and cross-boundary flows were

significant, a measure of coordination was essential.

The London

Health Planning Consortium

For these reasons approaches were made in 1977 to the four

Thames regions, the University of London and the University

Grants Committee. It was agreed that responsibility for health

service planning rested with the regions, but some matters

required the assistance of the university and medical schools,

and others a uniformity of approach. The regions retained their

reservations about the effectiveness of London-wide groups,

unless given power to ensure the implementation of decisions,

but accepted that some major decisions like the future of the

postgraduate hospitals were required before regional strategic

plans could be finalised. It was agreed that the proposed group

would only consider those issues requiring a London-wide

approach, and the London Health Planning Consortium was formed

at the end of 1977 to ‘identify planning issues relating to

health services and clinical teaching in London as a whole, to

decide how, by whom and with what priority they should be

studied; to evaluate planning options and make recommendations

to other bodies as appropriate; and to recommend means of

coordinating planning by health and academic authorities in

London'.

Dame Albertine Winner had retired from the civil service before

becoming the chairman of the Joint Working Group in 1967. The

Consortium, on the other hand, was chaired by a serving

departmental officer, Mr J C C Smith, and received considerable

support in the analytic work required from the Department of

Health. The membership included officers and representatives of

the four Thames regions, the University of London and the

University Grants Committee, the postgraduate hospitals and the

Department itself. It was not an executive body and decisions

continued to lie with the statutory health and academic bodies,

and where necessary with Ministers.6 Concurrently

the University of London was under increasing financial

pressure. To begin with it had not believed that it would

experience financial cuts, although prepared to consider how

best to maintain the quality of its medical and dental education

with so many clouds upon the horizon. The position worsened and

the principal of the university had to ask the deans how they

were not going to spend the money they were not going to get.

The Flowers working

party

In 1977, at the request of the University’s Joint Medical

Advisory Committee, the Conference of Metropolitan Deans set up

a working party to consider rationalisation. However this group

was unable to produce definitive recommendations even though

there was an acceptance of the need for change, and that the

number of medical schools might need to be reduced. As a result

the vice-chancellor established a major review of the resources

for medical and dental education in February 1979. It was

chaired by Lord Flowers, rector of the Imperial College of

Science and Technology. Lord Flowers’ working party started to

meet some time after the London Health Planning Consortium, and

it had to work to a tight timescale. Basic assumptions were that

the current intake of students and the existing level of funding

would be maintained, but that regard should be paid to

demographic trends and the Department of Health’s resource

allocation policy.

The Consortium’s reports

The London Health Planning Consortium faced two main problems.

It was widely accepted that there were many small and medium

sized units in specialties like cardiac surgery and

radiotherapy, and a degree of rationalisation was desirable. The

second problem was the need to reduce the level of acute

hospital services in central London, to bring it into line with

population and with the money likely to be available in the

future. J C C Smith, the Department Under-Secretary, established

a multi-disciplinary group of Department officials who were

smart, enthusiastic and enjoyed skunk work. They drove the

reports and provided the secretariat for the Regional

specialties studies. These were examined by groups with an

independent chairman, specialist expertise being supplied by

people who worked outside London and were less likely to be parti

pris, whilst local knowledge of the London hospitals was

available from consultants working in fields other than the one

under examination. Between 1979-1980 a series of reports were

published for consultation.

The level of acute services was

assessed by examining such factors as the demographic change in

population predicted over a decade, 1978 - 88, taking account of

changes in the distribution of population and its age structure,

hospital utilisation, admission categories, turnover interval

and length of stay. Account was also taken of the extent to

which people from outer London and beyond made use of hospitals

in central London, some of the difficulties posed by social

deprivation in inner London, and the shortcomings in London’s

non-acute services. This work was published in 1979 as a profile

of acute hospital services.10 It showed

how the progressive movement of population outwards had led to a

marked inequality of access to acute services in the Thames

regions, and - in

service terms - to

an over-concentration in central London. The study showed that

there might need to be reductions of the order of 20-25 per cent

in the number of acute beds, amounting in central London to cuts

of around 2,300 beds in all. The consortium suggested that if

this did not happen the health authorities in London would not

be able to find the resources to improve the standard of

services outside the acute sector, in the fields of geriatrics,

mental illness and mental handicap.

Changes of the order suggested would

be bound to have major implications for the medical schools. The

consortium proceeded to study the problem of providing

sufficient clinical facilities for medical education, in

parallel with the work of Lord Flowers’ working party. Two

Department officers, Steve Godber and Geoffrey Rivett, visited

all the deans of the London Medical Schools, to learn the size,

type, and specialty mix that schools needed for their student

intakes. Both groups published their reports on the same

day in February 1980. The consortium’s document, Towards

a Balance, suggested a pattern of hospitals

within which it would be possible to implement a variety of

educational options. It indicated ways in which complementary

hospitals in outer London, which were less affected by declining

population, might be linked with the various medical schools and

used for core teaching in medicine and surgery.

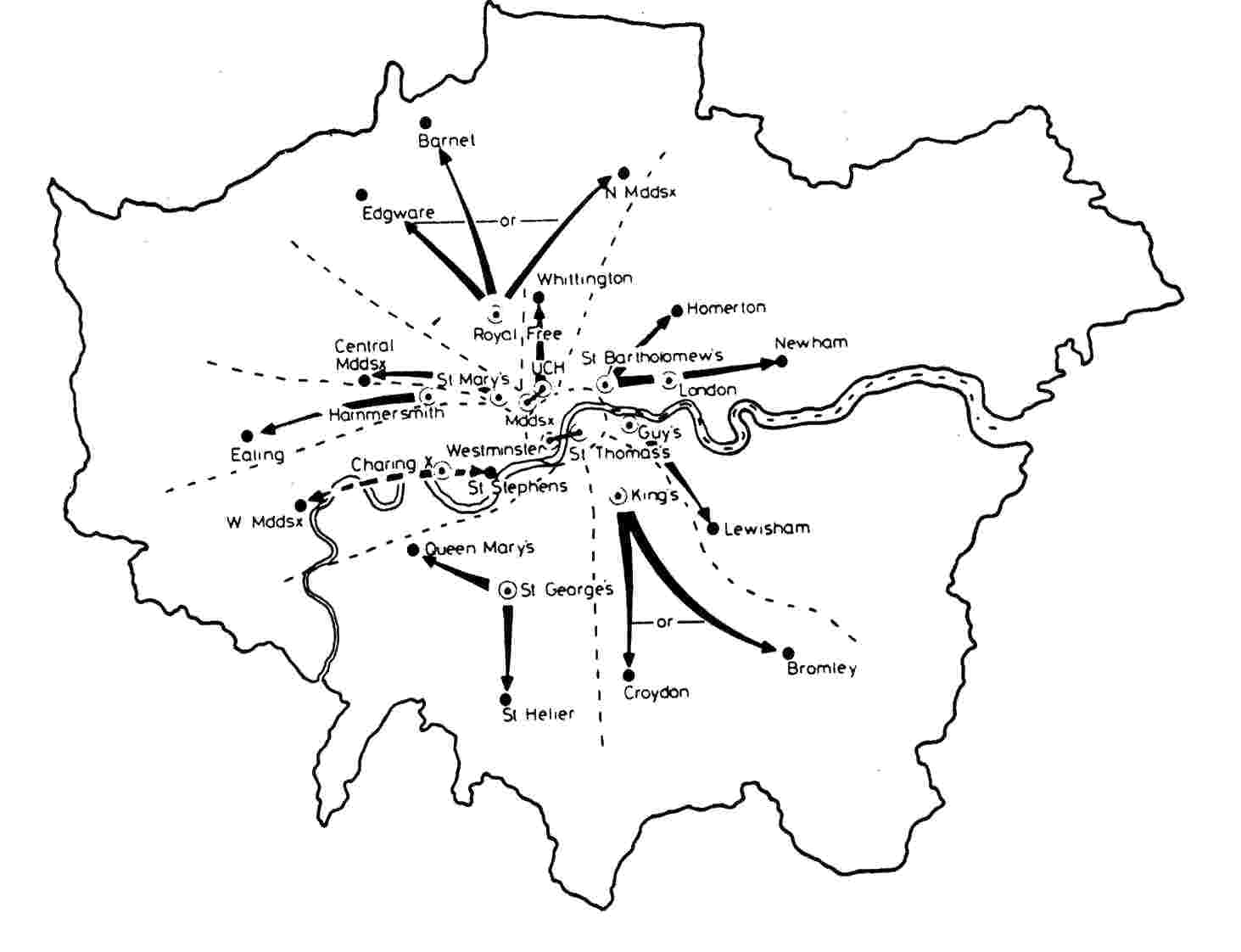

Towards a

Balance: relationship of teaching hospitals to large hospitals

in outer London. Source - Flowers Report and BMJ

8 March 1980. This

edition of the BMJ contains several articles on London hospital

planning

After the

publication of Lord

Flowers’ report it was discussed at a

conference at Senate House.9 Students

from the Westminster Hospital, parading with coffins, made their

views clear. The report suggested that there was over-capacity

in pre-clinical provision, and regarded it as axiomatic that the

University should use new buildings to the full, particularly as

these often lay in areas which remained predominantly

residential. A series of amalgamations was proposed as a result

of which 34 separate academic institutions would be grouped into

six schools of medicine and dentistry, some named after famous

doctors like Harvey and Lister. One protagonist suggested that

it was necessary to overcome ‘tribal loyalties’, a remark which

merely united the tribes in opposition.

A British

Medical Journal editorial expected that there

would be wide protest, indeed that "the the protests from each

institution under threat will merge into an unintelligible

Babel." Amongst the most controversial recommendations

were the closure of the pre-clinical school at King’s College,

Strand, and Westminster Medical School.9 Both

were bitterly and effectively opposed. Faced with such

opposition the University could not come to immediate decisions,

even though financial cuts were inevitable. The conflict spread

wider than the medical faculty, for there were consequences

affecting other institutions. In any case some recommendations

did not seem viable and the University’s joint medical advisory

committee produced a revised plan for restructuring London

medical and dental education which was likely to achieve wider

support. The modifications were accepted by the university joint

planning committee, but the Senate was divided and referred them

back. There was to be further delay. A new working party was

established chaired by the deputy vice-chancellor, Professor

Leslie Le Quesne, to examine the costs and savings which would

result from different patterns of closure and amalgamation.12 The

University employed management accountants to assist with this

costing exercise and in the meanwhile it encouraged those

schools wishing to proceed with closer association to do so.

The costing study necessarily made a number

of assumptions, some of which were open to challenge. In general

the high cost of running the newly built medical schools was

confirmed. Merging medical schools appeared to be more

cost-effective than merely phasing out a preclinical school. It

was also clear that agreement would not be achieved purely by

demonstrating that some solutions were cheaper than others.

Rationalisation in London and

changes in the organisation of medical education were now

overtaken by the events which led to the restructuring of the

National Health Service as a whole in 1982. The ever increasing

demand for resources and the financial problems arising from a

deteriorating economic situation were responsible for some

disillusion following the 1974 reorganisation. By 1976 there was

mounting criticism of a number of its aspects, particularly of

what many felt to be an unnecessarily complex and cumbersome

administrative structure. As a result the Labour government

established a royal commission which carried out an extensive

and wide-ranging study of the health service. It reported in 1979.13 The

Conservative administration which took office in May of that

year formally welcomed the report, but rejected one of the major

recommendations, previously proposed by three of the regional

chairmen, that regions should be accountable to Parliament for

matters within their competence. The proposal for an independent

enquiry into the health service in London was also rejected on

the ground that many of the issues were already under study by

the London Health Planning Consortium.

In general however the government

accepted recommendations aimed at improving and simplifying the

management and organisational structure of the health service. A

discussion document, Patients First, was

issued in December 1979, setting out proposals for the

simplification of the structure by removal of the area tier of

health authorities, which intervened between regions and health

districts, and for the strengthening of unit management by

greater delegation of authority to the operational level.

Instead, district health authorities were proposed, modelled on

existing ‘single district areas’ which had generally been judged

more effective than the areas which had the task of managing

several competitive districts.14 Internal

faction had been characteristic of a number of the area health

authorities in London.

The structure now envisaged would place the managing

authorities, the districts, close to the point of service

delivery, while maintaining regional

authorities for the purposes of strategic planning and resource

allocation. Patients First stated

that in London the government did not contemplate major changes

in regional boundaries in the next few years - in other words

the starfish arrangement would persist and a central London

health authority was not under consideration. It was also

suggested that there would be advantages in the establishment of

an advisory group, representative of major interests, to assist

the government in considering major issues in London.

In May 1980

the Secretary of State established this as the London Advisory

Group, chaired by Sir John Habakkuk (Principal of Jesus College,

Oxford; vice-chancellor of Oxford University, 1973-7) to report

to him and advise on the development of London’s health

services, and the restructuring of health authorities.15 Its

first task was to suggest guidelines for determination of

boundaries in London, a problem recognised as more complex than

elsewhere in the country. These appeared as an appendix to a

departmental circular on structure and management (HC(80)8). Two

further reports published early in 1981 proposed a strategy for

the future organisation of acute hospital services in London.15 They

recommended a reduction in the number of acute beds to free

resources for the elderly, the mentally ill and handicapped, and

for a variety of community services. The London Advisory Group

accepted the conclusions of the London Health Planning

Consortium, after examining its assumptions.

The

consortium had pointed to over-provision in relation to future

needs and had predicted that because of shortening length of

stay the same number of people could be treated in fewer beds.

The group reported that in two years that had elapsed since the

consortium’s calculations there had already been a reduction of

1,950 acute beds, nearly seven per cent, a more rapid rate of

decline than the consortium had projected.

Acute beds

in inner London

|

1977 |

28,600 |

|

|

1979 |

26,650 |

- 6.8

% |

|

1980 |

25,000 |

-

12.6 % |

|

LHPC target for 1988 |

22,500 |

-

21.3 % |

In contrast

to this fall the number of beds in private hospitals in inner

London was rising, more than doubling between 1977 and 1983 to

over 1,300. Some of the private hospitals were themselves

specialising, providing particular facilities like radiotherapy

or maternity and child care.

One of the

most significant statements made by the London Advisory Group

was that full use should be made of major hospitals, reductions

when necessary being made elsewhere, presumably in smaller

institutions. One region, North East Thames, had already been

pursuing this strategy, rationalising smaller hospitals and

building larger district general hospitals at Newham and

Homerton. This approach, which promised to free resources for

other uses, received the general endorsement of the Secretary of

State. Both economic

problems and the appreciation that London had more hospital beds

than could be justified led to a series of closures of small

hospitals where the accommodation was poor and other hospitals

nearby could pick up the load. As an example, in east

London, the Connaught Hospital was closed in 1977, the site

being sold in 1979 for £365,000. There were many

others including Poplar and the South London Hospital for Women,

the closures often being hard fought.

Major

hospitals of which full use should be made15

|

Charing Cross Hospital

|

Lewisham Hospital

|

St

Andrew’s, Bow

|

St

Stephen’s Hospital

|

|

Dulwich Hospital

|

The

London (Whitechapel and Mile End)

|

St

Bartholomew’s Hospital

|

St

Thomas’s Hospital

|

|

Guy’s

Hospital

|

Middlesex Hospital

|

St

Charles’ Hospital

|

University College Hospital

|

|

Hammersmith Hospital

|

Newham Hospital

|

St

George’s Hospital

|

Westminster Hospital

|

|

Homerton (Hackney)

|

Queen

Mary’s, Roehampton

|

St

James’ Hospital, Balham

|

Whittington (Royal Northern)

|

|

King’s College Hospital

|

Royal

Free Hospital

|

St

Mary’s Hospital, W2

|

|

Districting

The regions

were asked to submit proposals for the boundaries of the new

district health authorities to be established, taking the

guidance of the London Advisory Group into account. Because of

the tendency to propose a district to match every viable

district general hospital, the number of authorities created

proved to be considerable. At the Secretary of State’s request

the London Advisory Group considered the submissions. Work was

hampered by the fact that the University of London had not come

to final conclusions on the Flowers report. This was

particularly significant in the centre of London where hospital

catchments seldom matched local authority boundaries, and the

main academic institutions were sited. No ideal arrangement was

possible in inner London, whereas in outer London there were few

problems and in the main the regions’ proposals were accepted.15

The

university was considering the association of the medical

schools of Charing Cross and the Westminster Hospitals, which

led the North West Thames region to propose the establishment of

a single district to be known as ‘Riverside’ to be responsible

for both teaching hospitals. The university also suggested that

the medical schools of the Royal Free Hospital, University

College Hospital and St Mary’s should be grouped together. This

commanded little support in the committee established to

consider the proposition, all three medical schools preferring a

pairing which excluded St Mary’s. This opened another

possibility, a joint district to be known as Bloomsbury, to

manage the Middlesex and University College Hospitals. The two

teaching hospitals were close to each other, but lay on opposite

sides of a regional boundary and the idea was initially opposed

by the hospitals, the regions and the university.

The Secretary

of State was concerned to find a balance between the conflicting

requirements of coterminosity and practicability in health

service terms. His decisions differed in some respects from the

recommendations of the London Advisory Group.15 In

only one case was a district established which contained more

than one teaching hospital, Bloomsbury. Much work had gone

on behind the scenes over the previous months; the suggestion of

the amalgamation of the medical schools had been raised by

Department officers with the Deans of UCH and the Middlesex

Medical Schools and they had spoken to each other and the staff.

The University had been consulted and when it was clear that the

amalgamation was possible the Deans had seen the Secretary of

State. Similarly, off-the-record discussions took place with

Deans of the general teaching hospitals about the integration of

smaller postgraduate medical schools. The Westminster,

sure that it was secure, refused to consider turning itself in

part to a postgraduate centre. St Thomas' preferred

dermatologists to urogenital surgeons. Once the decisions were

announced they were accepted with good grace and an evident

desire to take advantage of the consolidation of two

undergraduate teaching hospitals and three postgraduate groups,

St Peter’s, the Royal National Orthopaedic and the Royal

National Throat, Nose and Ear hospitals. The grouping gave the

Bloomsbury district authority a worthwhile management task and

avoided the risk of separate authorities each bent on the

defence of its own institutions. In London as a whole

coterminosity remained a major feature. 27 out of 33 London

boroughs related to only one district and 18 were coterminous

with the matching health authority. Feelers to other

medical schools put out by the Department showed that the ground

was not fertile for other amalgamations.

With the

publication of the London Advisory Group’s last report its work

was complete, and it was disbanded in 1981 at the same time as

the London Health Planning Consortium.

The

decisions of the University of London

In December

1981, a year in which the University Grants Committee announced

a reduction in grant in each of the next three years, the

University of London finally reached conclusions on the pattern

of undergraduate medical education in London.17 It

was decided to reduce the number of separate schools, only four

remaining independent; the Royal Free, St Mary’s, St George’s

and King’s College Hospital Medical School which was in any case

uniting with King’s College Strand. Charing Cross and the

Westminster Medical Schools would be strengthened by merger; the

proposal by the medical schools of Guy’s and St Thomas’s to form

the United Medical Schools under a single governing body was

supported; the medical colleges of St Bartholomew’s and The

London should cooperate; and a joint school would be established

between the Middlesex and the Faculty of Clinical Sciences of

University College. The last would mirror Bloomsbury, creating

an academic organisation of considerable size and prestige. The

newly constructed medical school buildings at St George’s and

Charing Cross had proved expensive to run, largely because they

provided a much higher standard of accommodation. But they were

sited further from central London in the midst of large

residential areas, and it seemed only sensible to exploit this

advantage.

The

governance of the postgraduate hospitals

The

governance of the specialist postgraduate hospitals had been put

to one side in 1974. It was difficult to see where they might

best fit in to the reorganised health service. The 1972

reorganisation White Paper suggested that they should become

closely associated with other services in their vicinity, in

line with the recommendations of the Royal Commission on Medical

Education in 1968.18 The existing boards

of governors were preserved and continued to function under

earlier health service acts.

The old

antipathies between the specialist hospitals, which often formed

the focal point of a specialty unable to claim many beds within

a general hospital, and the undergraduate hospitals, persisted

in the form of a mutual wariness. The association suggested in

the White Paper had little appeal for the postgraduate

hospitals, which had branches in several parts of London and

seldom related clearly to a single region. To become too closely

involved with a general hospital carried the risk of merger and

ultimate extinction. Nevertheless, their future role required

examination and in 1976 the university established a working

party under the chairmanship of Professor Norman Morris to

review the academic institutes with which the postgraduate

hospitals were associated.

In March

1976, Dr David Owen suggested that a single authority might

integrate the planning and management, and rationalise the

services of three hospitals which lay next to each other: the

Hospital for Sick Children, Great Ormond Street, the National

Hospital for Nervous Diseases, and the Royal London Homeopathic

Hospital. A steering committee accepted the possibility of such

an arrangement, while pointing out the difficulties and

complexities which would be involved. Incorporation of

postgraduate hospital groups into area health authorities was

another possibility. The postgraduate hospitals made it clear

that the onus of justifying change lay upon those proposing it.

Led by Sir Reginald Wilson, the boards pointed out that their

activities spread far wider than the boundaries of any one

district, and some groups managed hospitals in two or three

different regions. They denied that planning arrangements with

the regions were inadequate, were well satisfied with the status

quo, and preferred to maintain their direct link with the

Department of Health and Social Security.

In September

1978 after several meetings and conferences, the Department

issued a discussion document which proposed the establishment

of a London postgraduate health authority.19 This

would take over the Department’s role in planning and resource

allocation, but would remain directly responsible to the

Secretary of State. The existing boards of governors would

remain in place for the time being. Other options were also

canvassed which involved the early disappearance of the boards,

but in the absence of consensus the DHSS preferred to temporise.

The proposal for an ‘overlord’ postgraduate health authority was

regarded by the hospitals as very much second best; they

preferred the status quo. The idea was criticised in the House

by Mr. Patrick Jenkin as the insertion of a further tier of

management when simpler structures were in fact required.

Shortly afterwards, in May 1979, a Conservative government was

elected and Mr. Jenkin became Secretary of State for Social

Services. It was then decided to take no action until reports of

the Flowers working party9 and the Royal

Commission on the National Health Service13 were

available.

The London

Advisory Group considered the management arrangements of the

postgraduate hospitals in 1980 and visited all of them. The

university was considering the possibility of merging some

institutes with medical schools, but where it proposed to

maintain a separate university institute this argued for the

maintenance of an independent authority. The presence of

university representatives on the London Advisory Group was

therefore important, so that all could be made aware of the way

university thinking was developing. In its report, the London

Advisory Group distinguished between hospitals which were to be

rehoused in close association with general hospitals, or where

the matching institute was likely to be merged with a general

medical school as a result of the decisions following the

Flowers report; and those which were unlikely to move from their

existing sites and where the institute was likely to continue in

its present form for the foreseeable future.15 It

recommended that the first group should be managed by the

appropriate district health authority from 1 April 1982.

Hospitals in the second category, in general the larger ones

with more viable institutes, should be managed by newly

established special health authorities in place of the existing

boards of governors. Following consultation, the Secretary of

State established special health authorities for six groups, and

for the Hammersmith Hospital. The Hospitals for Sick Children,

the Royal Marsden, the National Hospitals for Nervous Diseases,

Moorfields, Bethlem Royal and Maudsley, and the National Heart

and Chest Hospitals, remained independent of the regional health

authority structure. The Hammersmith, associated with the Royal

Postgraduate Medical School, while wishing to remain accountable

to the North West Thames region, found to its surprise that it

was reconstituted as a special health authority. Department

officers visited teaching hospitals such as St Thomas', the

Westminster and the Middlesex, trying to find an appropriate and

willing partner that would maintain the excellent features of

these small posstgraduates. The advantages of taking on a unit

of prestige - and its budget - were not lost on some hospitals,

and St Thomas' was a willing host for the skin hospitals.

Others, such as the Westminster, felt they were in need of

neither advice, nor help, nor a new unit and lost the

opportunity. Four groups came under the

management of a district authority: the Royal National

Orthopaedic Hospitals, the Royal National Throat, Nose and Ear

Hospitals, the St Peter’s group and St John’s Hospital for

Diseases of the Skin. The first three came under Bloomsbury, and

St John’s under West Lambeth where it was likely to be relocated

(within St. Thomas' Hospital).16 Decisions

on the Eastman Dental Hospital and Queen Charlotte’s were

postponed.

During the

months preceding the restructuring of the health service on 1

April 1982, chairmen and members were selected for the new

district authorities and new officer teams were appointed. Once

again management was to operate by consensus. Certain teaching

districts were designated: those deeply involved in medical

education because they managed the main university hospital used

by a medical school.20 Some of the

medical schools prepared the private legislation needed to unite

independent institutions, in line with the university’s

proposals.

The pattern

of the acute services was changing; small hospitals were

closing, small accident and emergency departments were

disappearing. Evolution was assisted in some places, like

Bloomsbury, by the way in which restructuring changed the

responsibilities of authorities. Amalgamation and

rationalisation, the chosen tools of the King’s Fund in earlier

years, were once more the order of the day. Health authorities

now, for financial if for no other reasons, had to grasp the

nettle of reshaping the hospital services in central London more

closely to national priorities. The pace of change was

increasing, major hospitals felt threatened, and in fighting for

survival might urge the closure of competitors. King's

College Hospital, in particular, was under assault..

1 Machiavelli

N. Il Principe. Rome, Antonio Blado, 1532.

2 Great Britain, Parliament. National

Health Service reorganisation: England. London, HMSO, 1972. Cmnd

5055.

3 Great Britain, Department of Health

and Social Security. Management arrangements for the reorganised

National Health Service. London, HMSO, 1972.

4

Great Britain, Department of Health and Social Security. The NHS

planning system. London, DHSS, 1976; Great Britain, Department

of Health and Social Security. Priorities for health and

personal social services in England: a consultative document.

London, HMSO, 1976; and Great

Britain, Department of Health and Social Security. The way

forward: further discussion of the Government’s national

strategy based on the consultative document - Priorities

for health and personal social services. London, DHSS, 1977.

5 Great Britain,

Department of Health and Social Security. Sharing resources for

health in England: report of the resource allocation working

party. London, HMSO, 1976; and Ranger

D. RAWP. University of London Bulletin no 41, May 1977.

6

Great Britain, Department of Health and Social Security. On the

state of the public health. Annual report of the Chief Medical

Officer for 1979. London, HMSO, 1980; The Times, 26 February

1980; and British

Medical Journal, 1980, i, p 723.

7 Joint survey of medical and surgical

services in the county of London. London, P and S King and

London County Council, 1933.

8 Rationalisation of services: a revised

hospital plan for inner London. London Co-ordinating Committee,

1975. (LCC(75)13); Sunday Times, 23 November 1975; and Hospital

and Health Services Review, February 1976.

9 London

medical education. A new framework: report of a working

party on medical and dental teaching resources. (Chairman: Lord

Flowers). London, University of London, 1980; University of

London press release, February 1979.

10 London Health Planning Consortium. Acute hospital

services in London. London, HMSO, 1979.

11 London Health Planning Consortium. Towards a

balance. London, DHSS, 1980; and British Medical Journal, 1980,

i, pp 665-6, 734-5.

12 Great Britain, Department of Health and Social

Security. On the state of the public health. Annual report of

the Chief Medical Officer for 1980. London, HMSO, 1981.

13 Royal Commission on the National Health Service.

Report. (Chairman: Sir Alec Merrison). London, HMSO, 1979. Cmnd

7615.

14 Great Britain, Department of Health and Social

Security and Welsh Office. Patients first: consultative paper on

the structure and management of the National Health Service in

England and Wales. London, HMSO, 1979.

15 Reports of the London Advisory Group. London,

1981.

1 Acute

hospital services in London;

2 District

health authorities in London;

3 Management

arrangements for the postgraduate specialist teaching hospitals;

4 The

development of health services in London.

16 Great Britain, Department of Health and Social

Security. On the state of the public health. Annual report of

the Chief Medical Officer for 1981. London, HMSO, 1982.

17 Joint planning committee of the University of

London on medical education in London. Report. London,

University of London, 1981.

18 Royal Commission on Medical Education 1965-8.

Report. (Chairman: Lord Todd). London, HMSO, 1968. Cmnd 3569.

19 Great Britain, Department of Health and Social

Security. The future management of the London specialist

postgraduate hospitals. London, DHSS, 1978.

20 The membership of district health authorities,

HC(81)6 Appendix 5; see also HC(82)2 Appendix 2.

|